Carl Andre, Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, Wade Guyton, Seth Price, Kelley Walker, John Armleder, Ei Arakawa, Felix Gonzalez-Torres

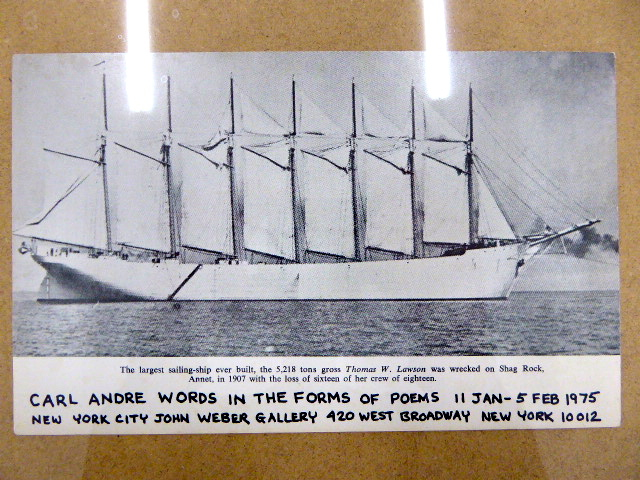

Carl André

Words in the form of poems

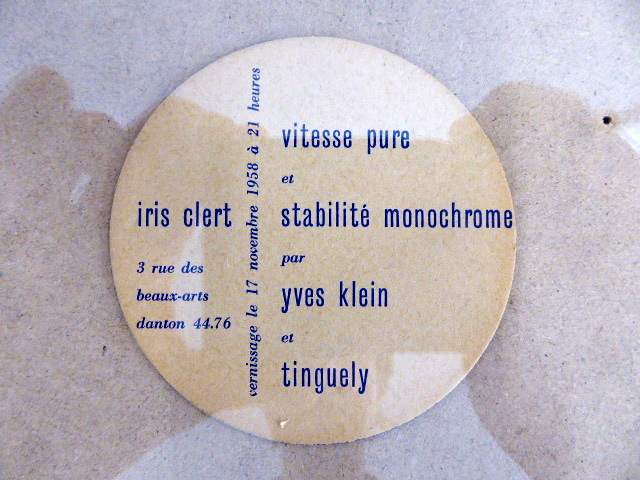

Yves Klein-Jean Tinguely

Vitesses pure

Stabilitié monochrome

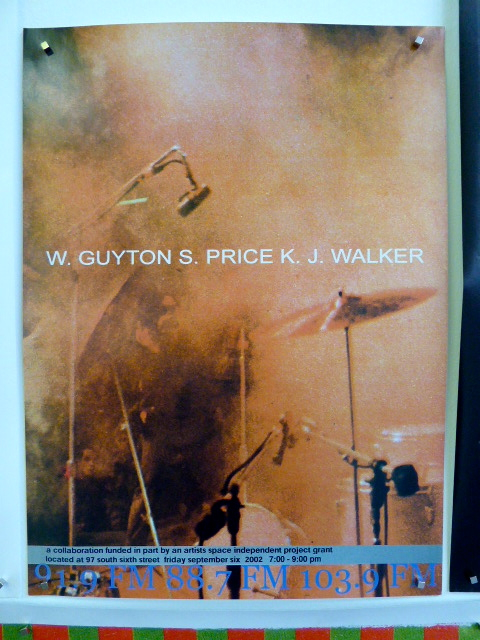

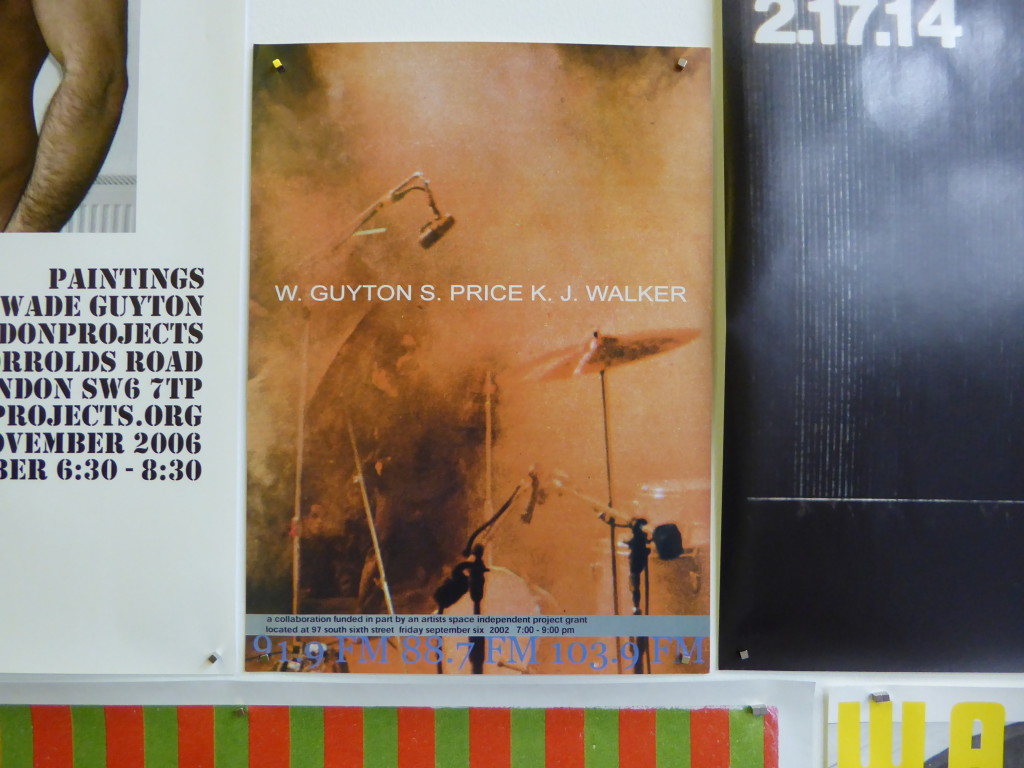

W. Guyton S. Price K.J. Walker

a collaboraton founded in part by an artist space

independent project grant

located at 97 south street friday september six 2002 7:30pm-9:00pm

91.9 FM 88.7 FM 103.9 FM

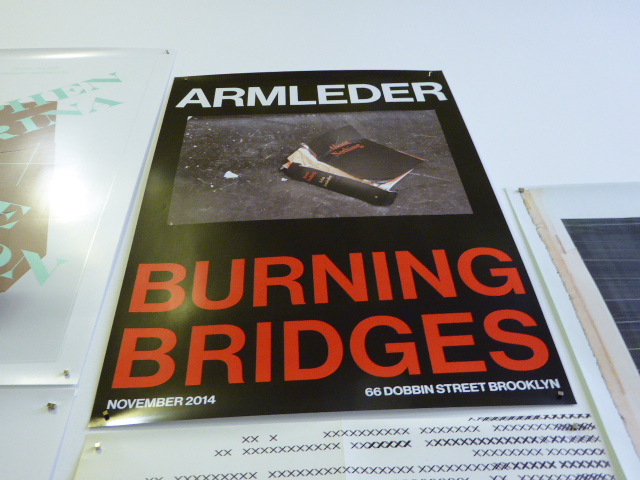

John Armleder

Jungle All The Way

Ei Arakawa

M.A.V.O.E (killer COMMERCIAL)

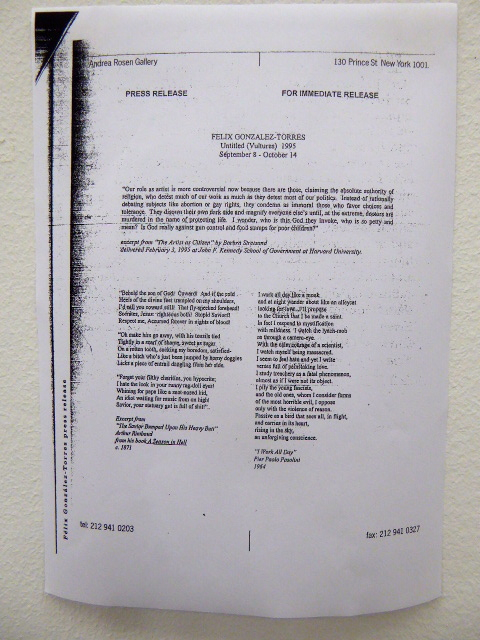

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Unitled (Vultures) 1995

Uploaded by Jeanne Graff

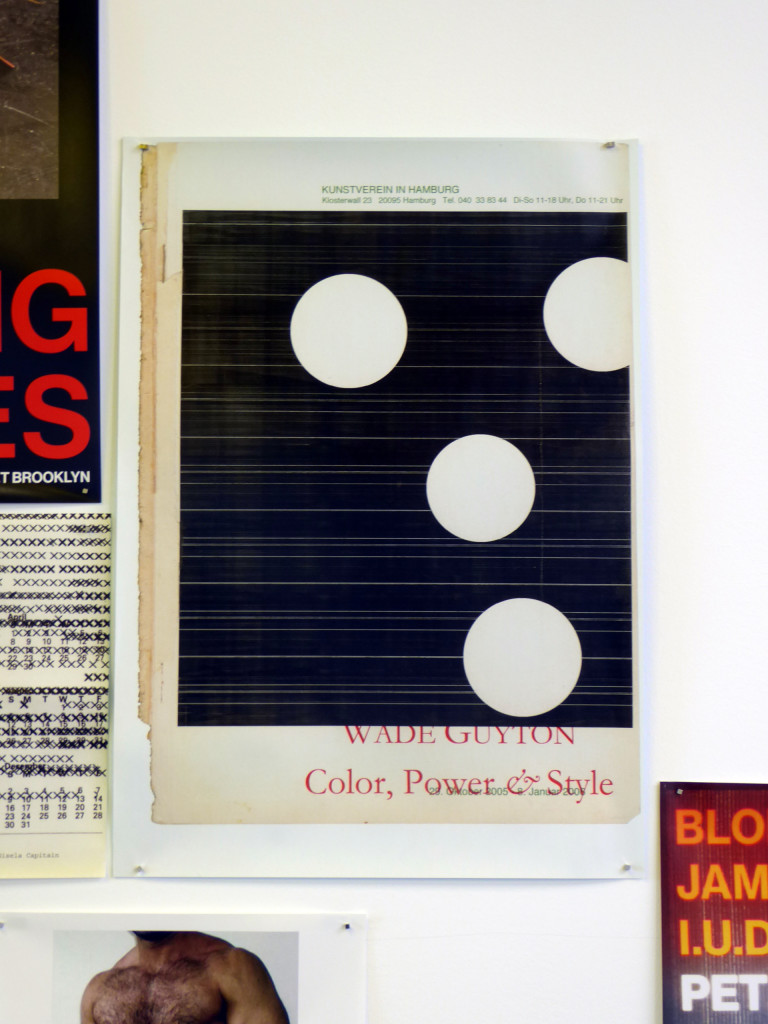

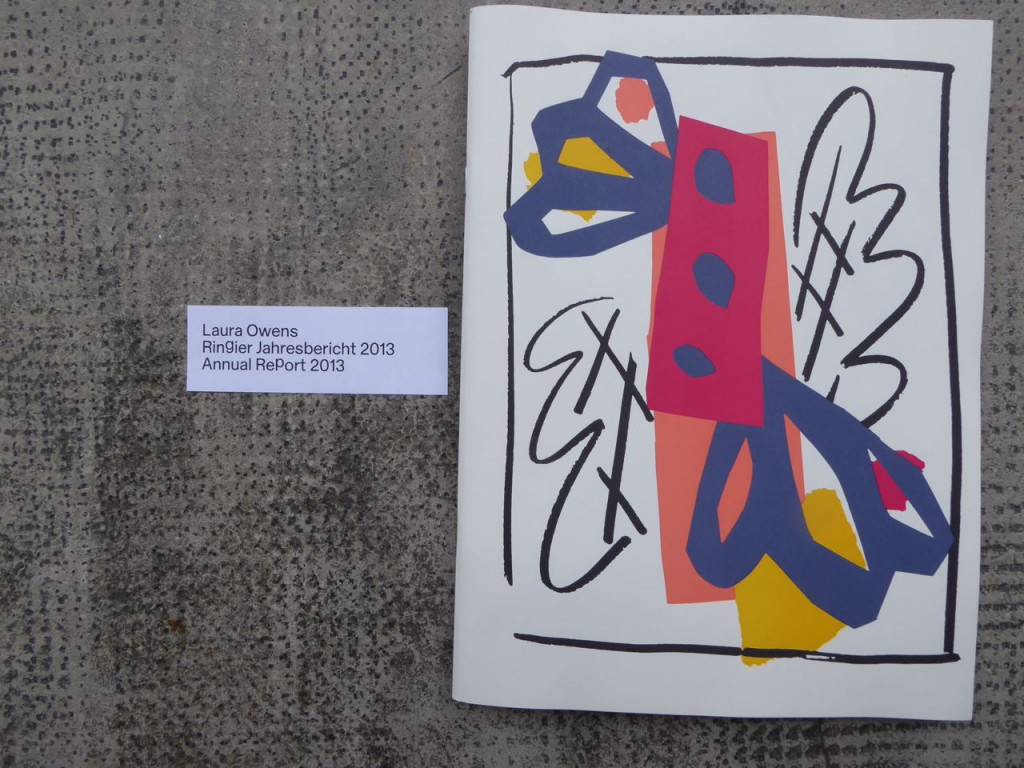

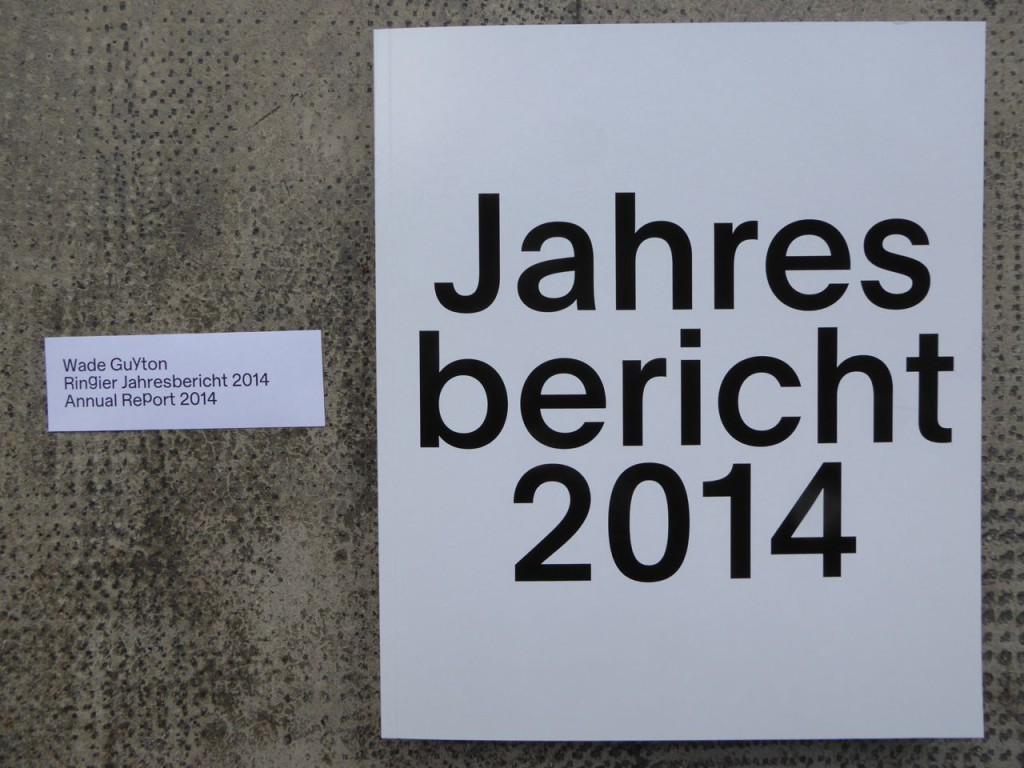

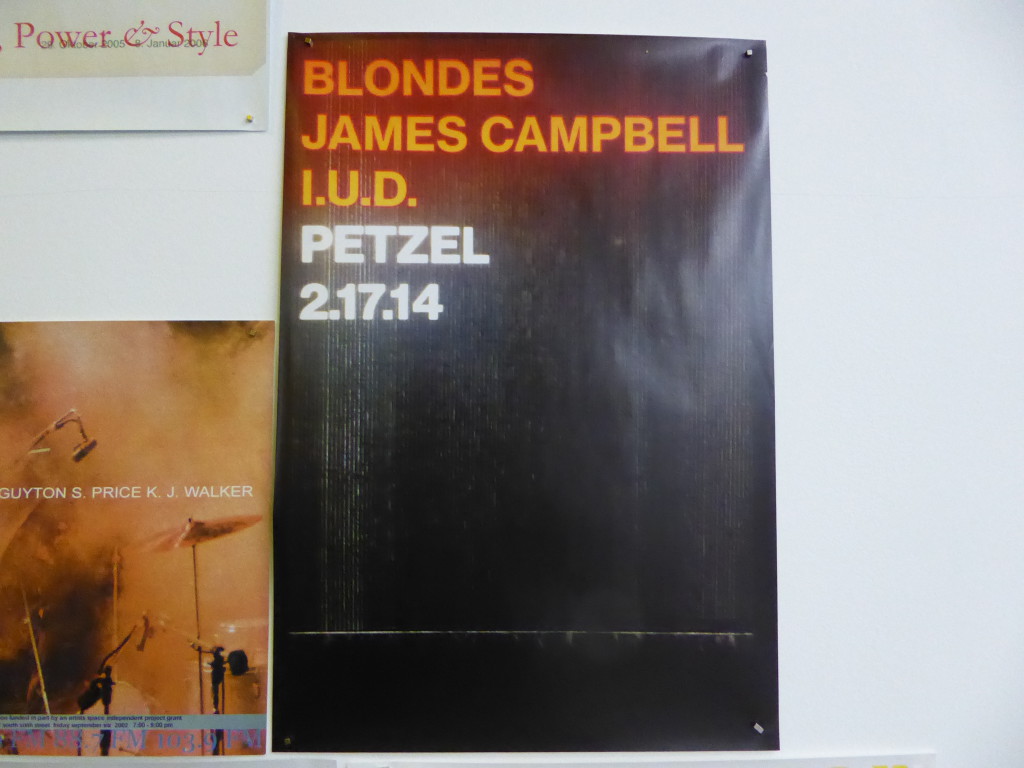

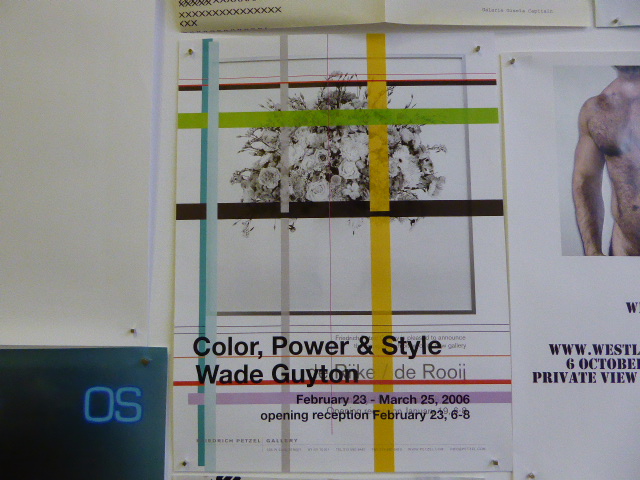

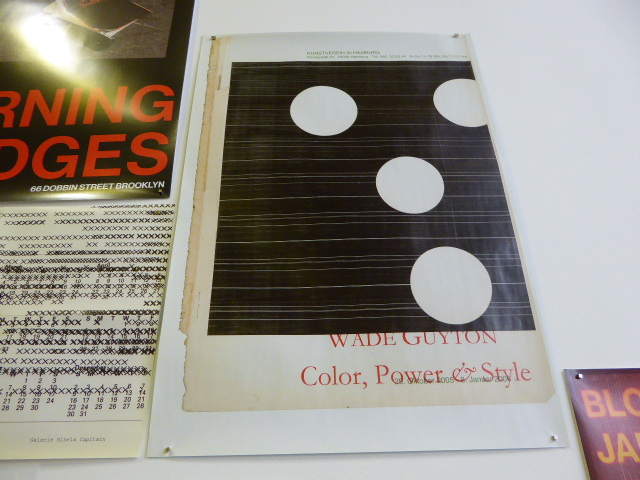

Wade Guyton: Color, Power & Style

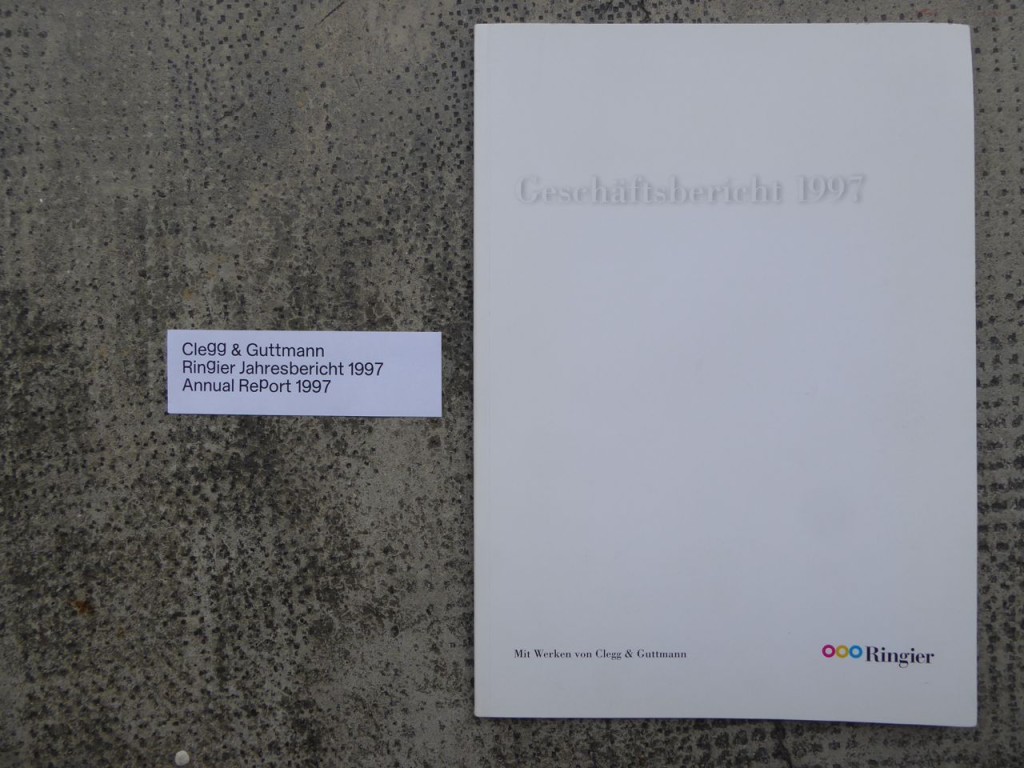

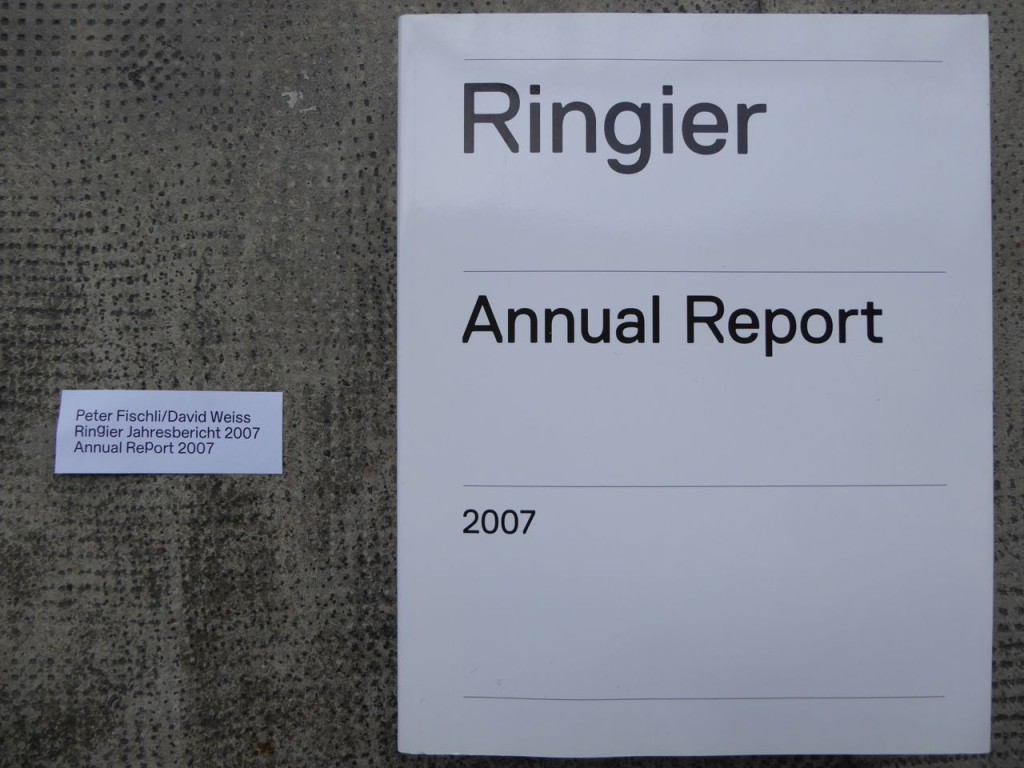

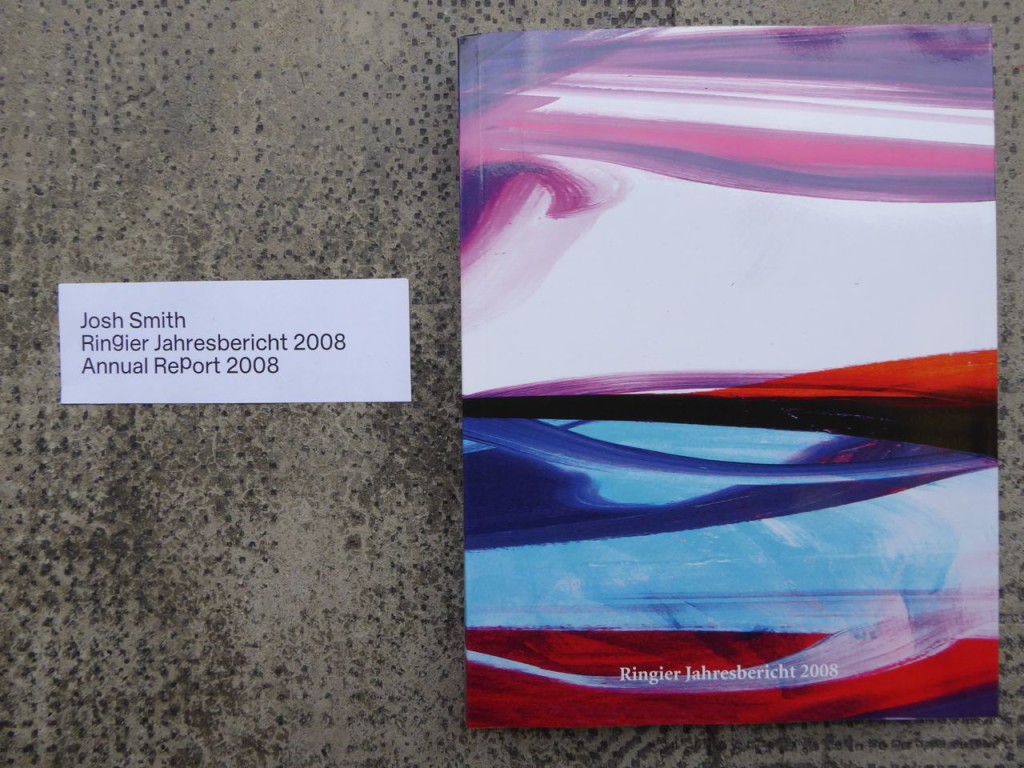

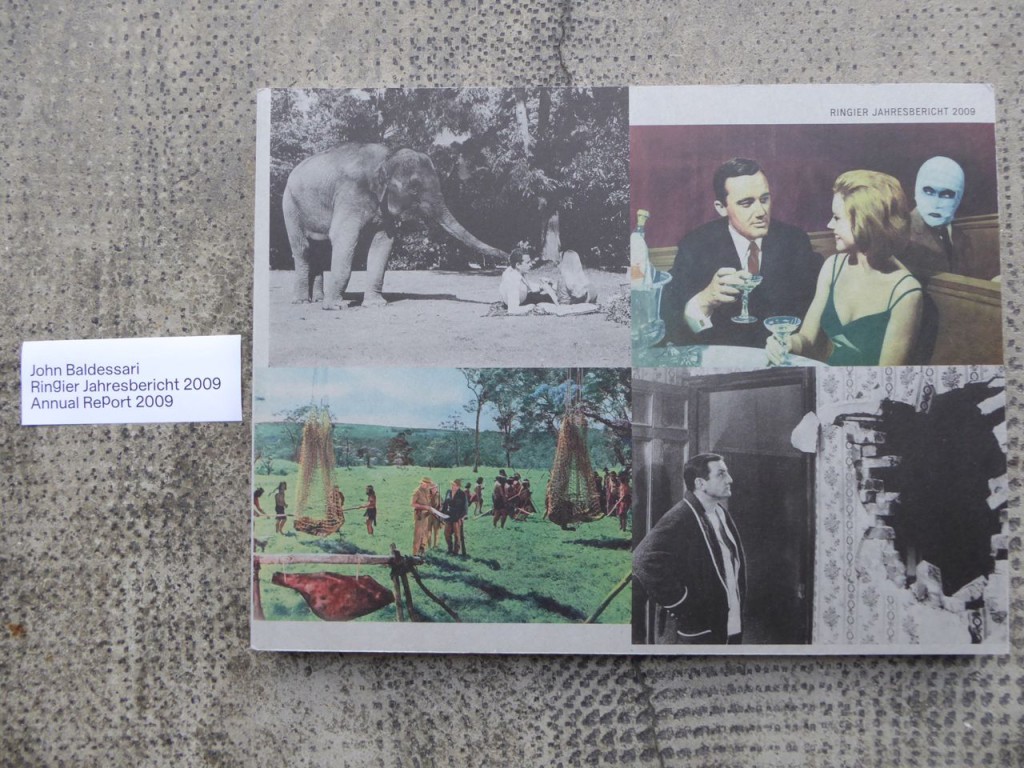

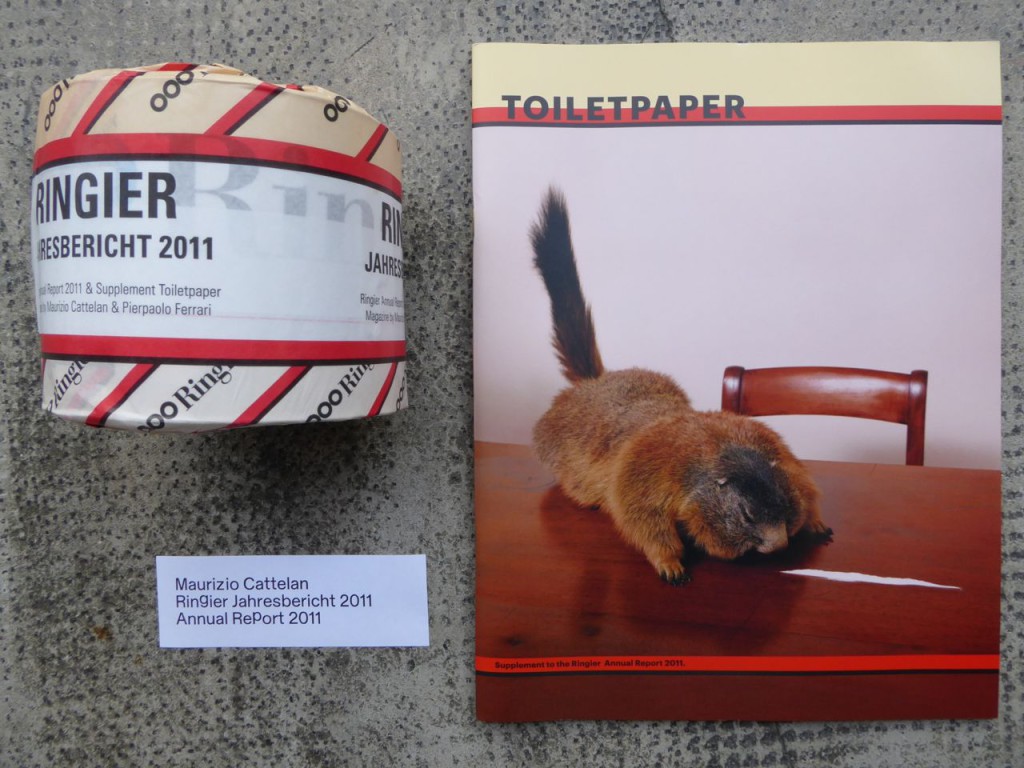

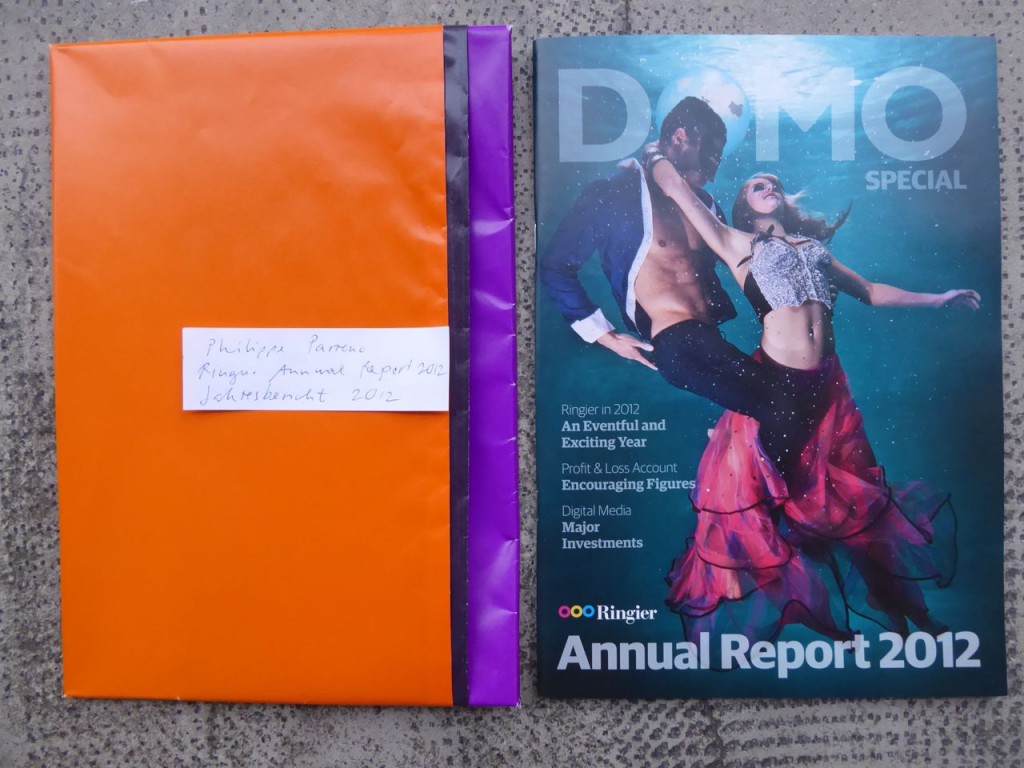

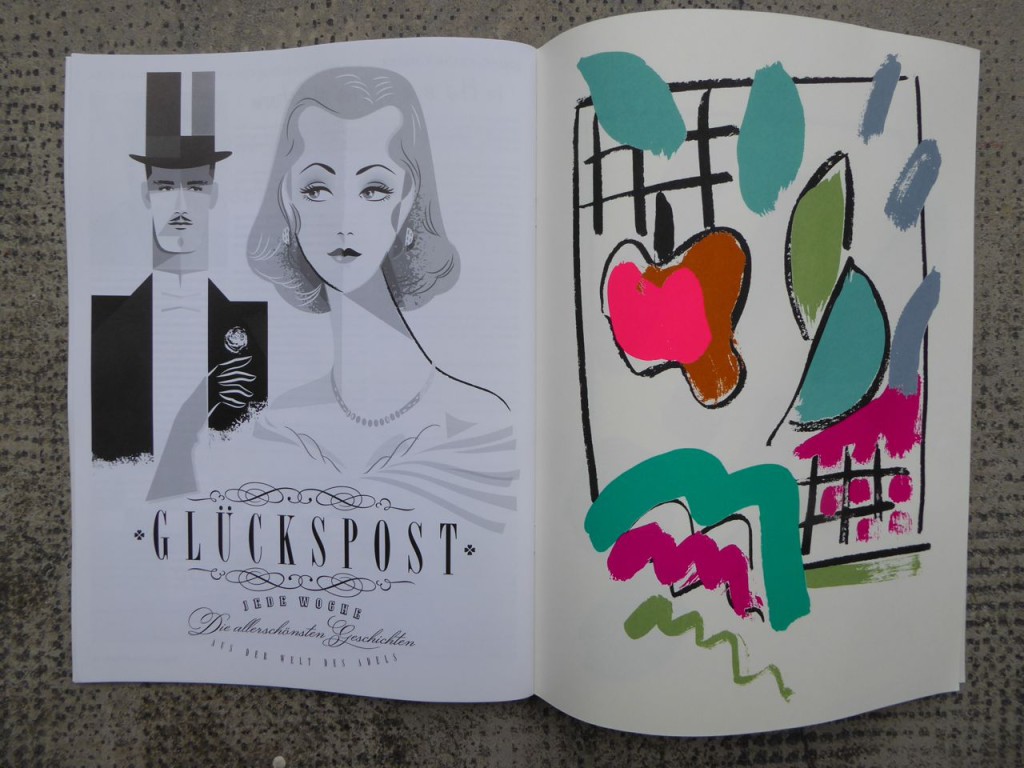

Ringier Annual Report / Ringier Jahresbericht 1997-2014

Ringier Annual Report

Daniel Baumann. Interview mit Beatrix Ruf

erschienen in Englisch und Italienisch in MOUSSE, #19 – 2009

English version see below

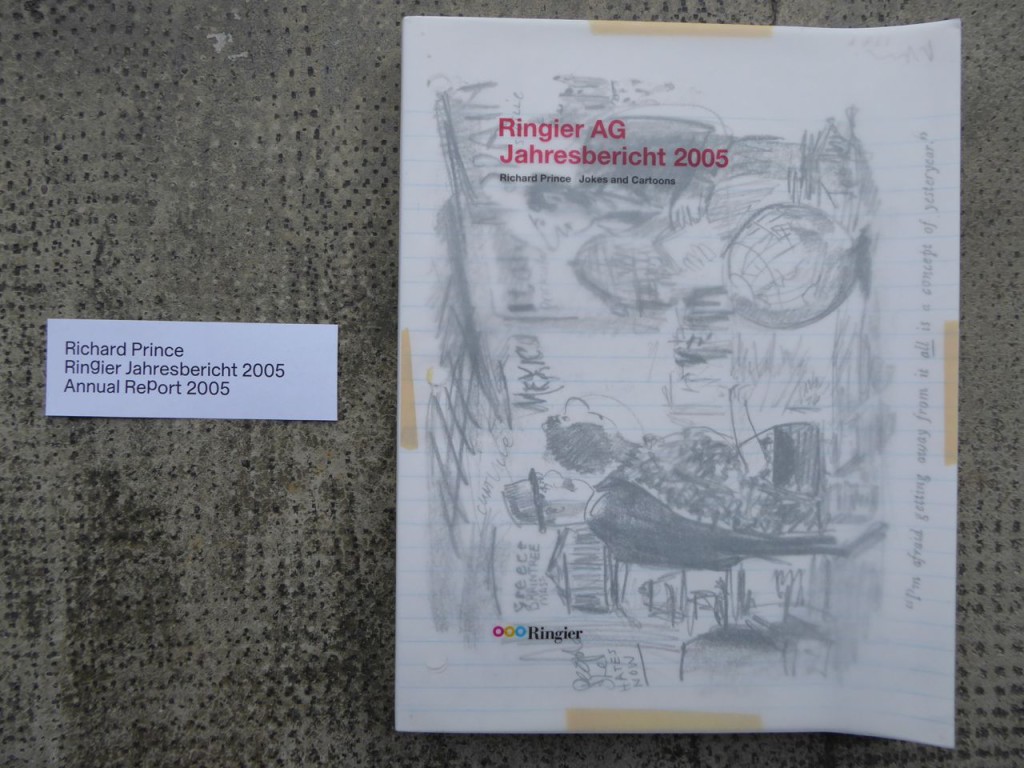

Die Ringier Annual Reports, seit 1997 von namhaften Künstlern gestaltet, ist eine interessantesten, grosszügigsten, zweifelhaftesten und abgeklärtesten Publikationsreihen des Jahrzehnts. Jeder Annual Report des multinational tätigen Medienunternehmens ist Künstlerbuch und Werbebroschüre und Treffpunkt (oder Tanzfläche) für Widersprüche. Das Künstlerbuch als Ort der Selbstermächtigung und Selbstbestimmung wird hier zur Kommunikationsplattform eines Familienunternehmens, dem der Traum der Selbstbestimmung auch nicht fremd ist. Der freie Künstler trifft somit auf den freien Unternehmer, beide spiegeln sich in ihrem Wunsch nach Unabhängigkeit, wobei der Unternehmer für die Freiheit des anderen zahlt und dafür Kunst, Diskussion und Aufmerksamkeit kriegt. Clegg & Guttmann haben 1997 den Auftakt gemacht, ihnen folgten Sylvie Fleury, Christian Philipp Müller, Harald F. Müller, Liam Gillick, Aleksandra Mir, Christopher Williams, Matt Mullican, Richard Prince, Richard Phillips, Peter Fischli/David Weiss und nun Josh Smith.

Die Ringier Annual Reports erscheinen in drei Sprachen in einer Auflage von mehreren Tausend Exemplaren und werden gratis verteilt. Jede Publikation ist anders, aber alle Künstler haben versucht, ihre Licence zur Freiheit auszunutzen und dabei ihre Instrumentalisierung einzuberechnen. Einzig Richard Prince schien sich um das Ganze zu foutieren und Josh Smith ist ähnlich vorgegangen. Als Publikationsreihe sind die Ringier Annual Reports Porträt und Ballade gegenseitiger Abhängigkeit, sie sind Abbild und Teil der zu Ende gehenden Finanzdekade und ihrer Parallelwelt und gleichzeitig können sie in ihrer fast perversen Transparenz als Alternative dazu verstanden werden.

Ich wüsste nicht, mit welcher Publikationsreihe sie sich in ihrer Zweideutigkeit und Hybridität besser vergleichen liessen, als mit Psychopathology and Pictorial Expression. An International Iconographical Collection. Diese wurde zwischen 1963 und 1977 vom Schweizer Pharmakonzern Sandoz herausgebracht, um ihr Neuroleptica Melleril zu promoten. Jede Ausgabe war einem Aussenseiterkünstler oder einem bestimmten Thema (“Children’s Drawings and their Bearing of the Doctor-patient Relationship”) gewidmet und setzte sich aus einem kulturhistorisch-wissenschaftlichen Text und 10 luxuriösen Bildtafeln zusammen. Psychopathology and Pictorial Expression erschien wie Ringier Annual Reports in mehreren Sprachen und wurde ebenfalls gratis verteilt, in diesem Fall an Ärzte und Psychiater. Die Reihe war gleichermassen einem humanistischen Menschenbild und dem Willen zur Gewinnmaximierung verpflichtet und spiegelte die bürgerlich-kapitalistische Sehnsucht nach Versöhnung der beiden Sphären. Gleichzeitig war sie ein Beitrag in der Diskussion um die Grenzen zwischen krank und gesund, die damals analog zum Kunstbegriff neu formuliert wurden.

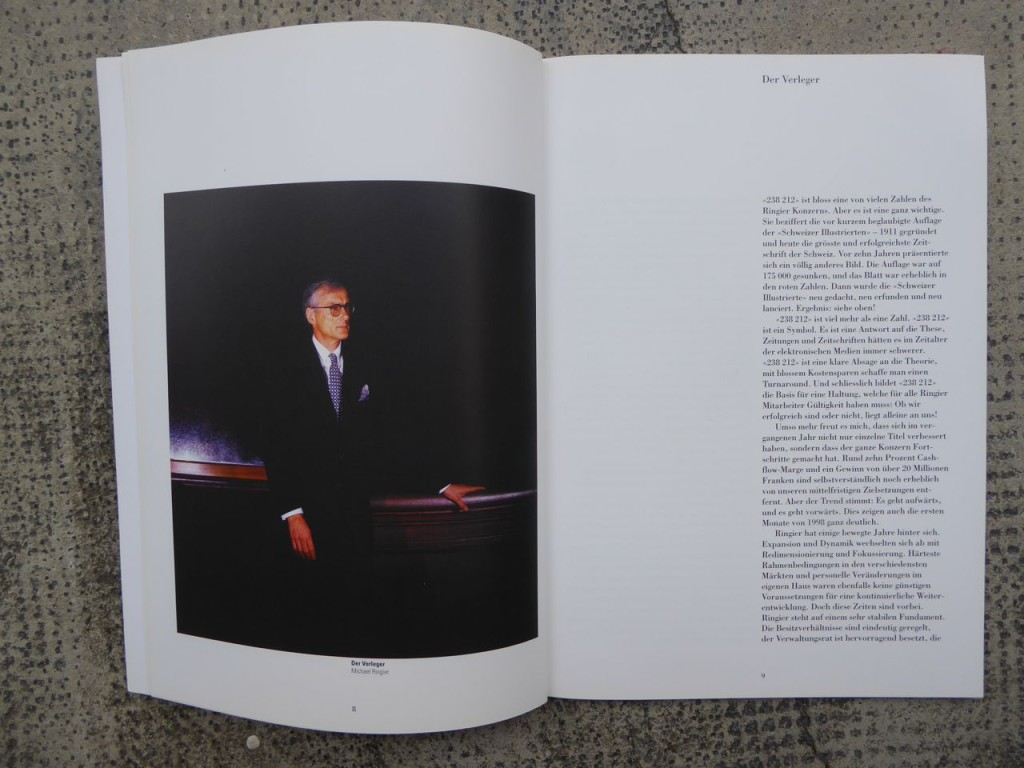

Im Unterschied zu Ringier, wollte sich Sandoz jedoch nicht auf dem Gebiet der Kunst profilieren. Denn Ringier ist nicht nur ein international tätiges Medienunternehmen, sondern mittlerweile auch ein wichtiger Akteur in der Kunstwelt. Michael Ringier hat im Verlauf der letzten Jahre für seine Firma eine bedeutende Sammlung zeitgenössischer Kunst aufgebaut. Beraten wird er dabei von Beatrix Ruf, der Direktorin der Kunsthalle Zürich, die wiederum die Jahresberichte kuratiert. Zudem ist Ringier 2004 mit dem kleinen, 1994 in Genf gegründeten Verlag Verlag JRP (Just Ready to be Published) eine Geschäftsbeziehung eingegangen und hat ihn mit Hilfe ihres Gründers Lionel Bovier zu einem der führenden und renommierten Verlage für zeitgenössische Kunst ausgebaut. 2006 kam schliesslich die Kunstzeitschrift Monopol dazu. Anfang Mai habe ich Beatrix Ruf in Zürich getroffen, um mehr über die Ringier Annual Reports zu erfahren.

Beatrix Ruf: Bis heute ist es ein Projekt in Prozess. Die Idee kam uns in New York, in der Galerie von Colin de Land, wo wir 1996 Arbeiten von Clegg & Guttmann gesehen haben. Seit einem Jahr diskutierten Michael Ringier und ich über die Ausrichtung der Sammlung. Er und seine Frau Ellen haben ja bereits eine tolle Sammlung von Papierarbeiten der Avantgarde um 1900. Er wollte nun ganz dezidiert eine Sammlung für die Firma aufbauen, sehr langfristig gedacht und mit den für Firmensammlungen immer diskutierten Ideen wie man Kunst in den Firmenalltag integrieren könnte, was dies für die Mitarbeiter bedeutet usw. Ich stehe dieser Vorstellung in einem gewissen Sinne kritisch gegenüber, weil ich denke, dass man keine Kanten abschleifen und Kompromisse eingehen sollte. Spontan haben wir uns gefragt, ob nicht genau diese Jahresberichte eine Möglichkeit wären, eine bestimmte Form von künstlerischer Praxis zu integrieren, eine Sondersituation des Geschäftsberichts zu initiieren, die für die Mitarbeiter und die Künstler natürlich auch eine Sondersituation werden würde. Der erste Jahresbericht von Clegg & Guttman war gelinde gesagt eine Katastrophe. Sie arbeiten mit Fotografie, und man hat sie mit den sonst für Geschäftsberichte ungeheuerten Fotografen verwechselt. Als Clegg & Guttman kamen dachten alle, jetzt kommen sie wieder zum jährlichen Fotografien. Die zwei haben aber extreme Settings aufgestellt, mit klaren Kleidervorschriften, dunkler Anzug, weisses Hemd, rote Krawatte, die uniformierten Insignien der Autorität und Macht. Sie leuchten die Szene mit einem extremen, fast unerträglichen Licht aus, um starke Kontraste zu erhalten und historische Malerei zu evozieren. Ausserdem haben sie ausschliesslich die Kaderebene porträtiert, was ein Tabubruch war – es gab Opposition, aber auch sehr interessante Diskussionen. Clegg & Guttman haben ihre Methode nicht offengelegt, andererseits war aber bei diesem ersten Projekt noch nicht vollständig klar wie weit die Künstlerinnen und Künstler wirklich in das Erscheinungsbild der Firma eingreifen dürfen.

Daniel Baumann: Und beim nächsten Annual Report?

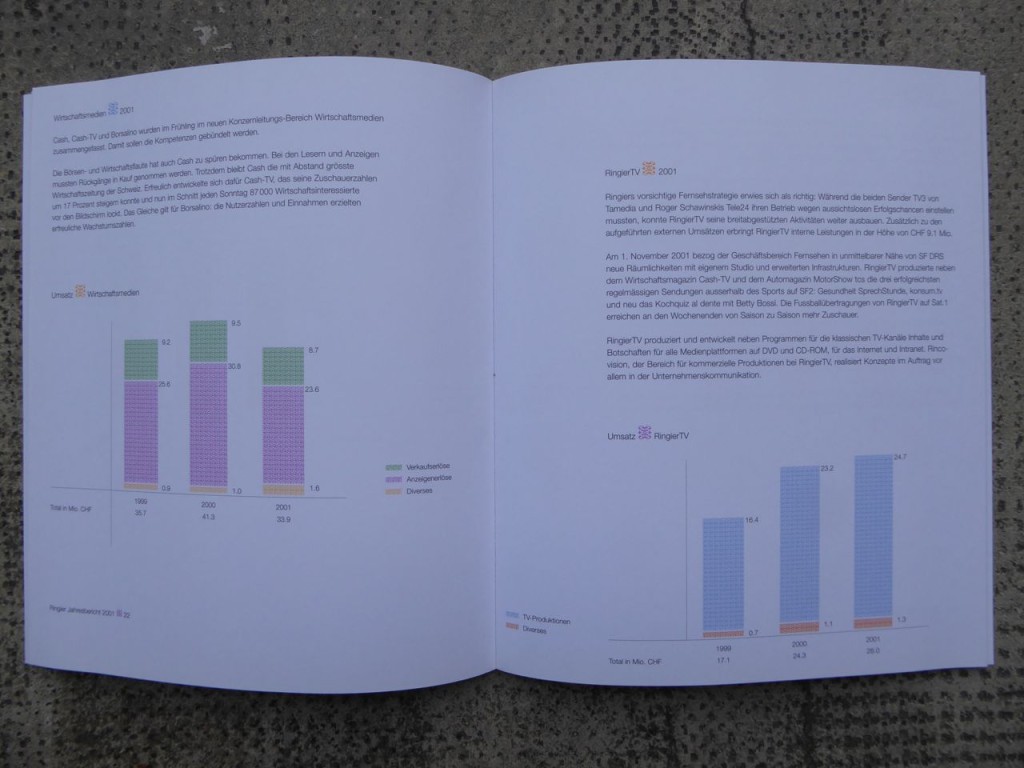

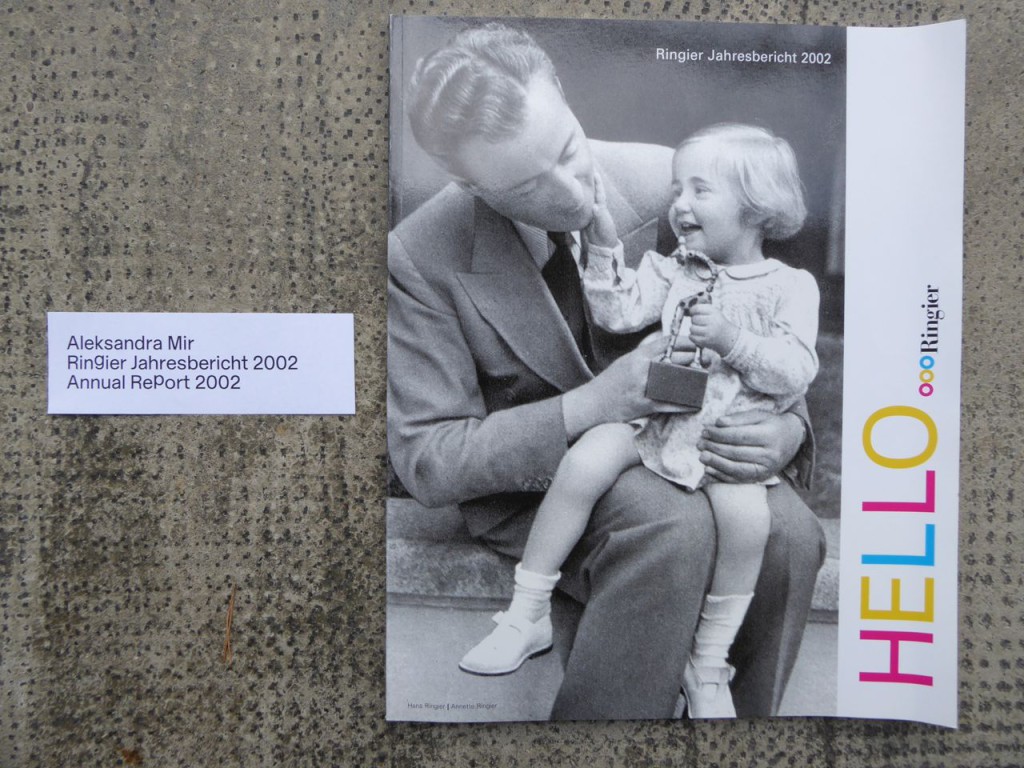

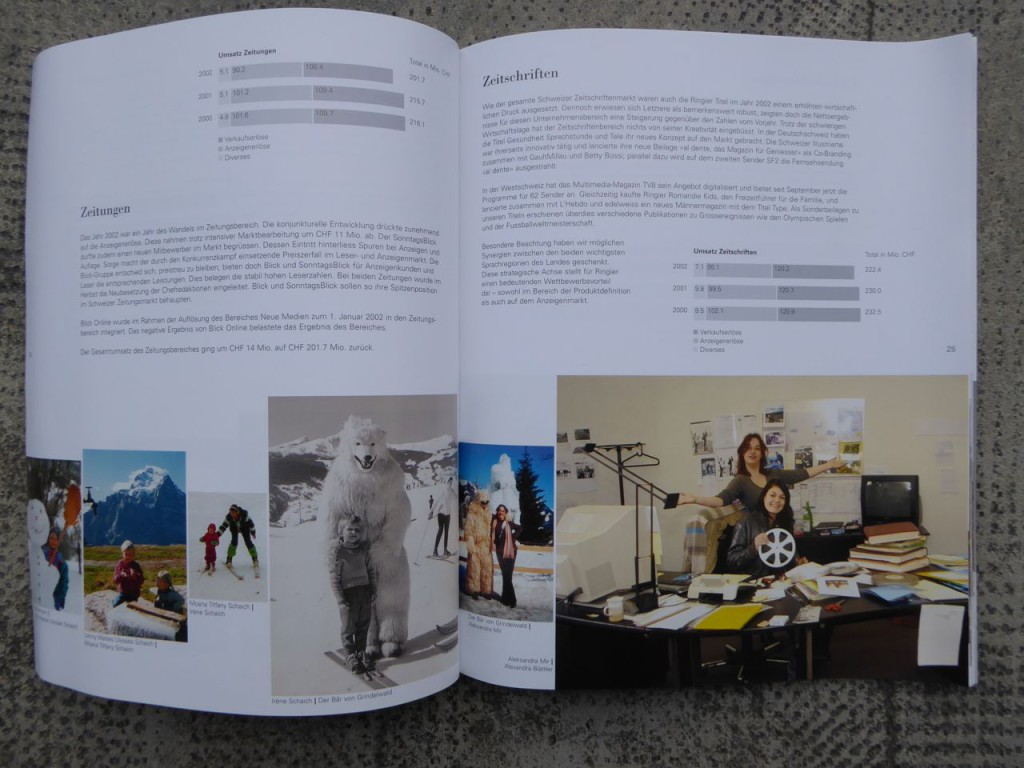

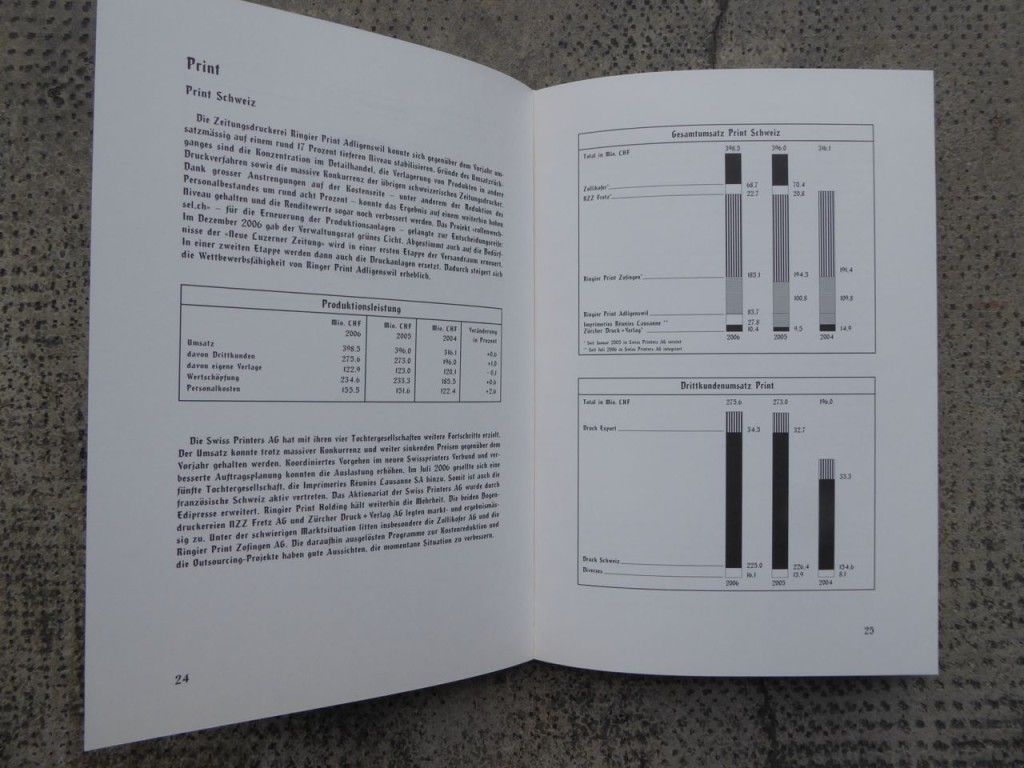

BR Da war die Carte Blanche vollständig etabliert, es gab keine Vorgaben bezüglich Format, Gestaltung und Inhalt mehr, ausser natürlich, dass die Zahlen und Berichte aufgeführt und lesbar waren. Viele haben im und mit dem Archiv der Firma gearbeitet, zum Beispiel Aleksandra Mir oder Matt Mullican, der das digitale Bildarchiv der Firma mit einem von ihm eigens entwickelten System katalogisierte: Er hat eine Art Kosmologie des digitalen Bildarchivs entworfen und ein Berechnungsmuster entwickelt, um herauszubekommen, wieviele Bilder man auf einer Seite abbilden musste, um eine Art Grundausleuchtung des digitalen Archivs in der analogen gedruckten Form zu erhalten. Christian Philipp Müller wiederum ist ein gesamtes Jahr im Auftrag der Firma gereist und hat sämtliche Tätigkeitsorte der Firma abgeklappert. Er ist als fiktiver investigativer „Journalist“ aufgetreten, und hat eine Art Hybrid zwischen Länderporträt, Aufdeckungsgeschichte und Reiseführer geschaffen. Das hat zu vielen Diskussionen geführt, weil er auch Klischees reproduziert hat und sich Länder zu „typisch“ und so in ihren Augen falsch dargestellt fanden, aber er hat auch eine grosse Verbindlichkeit und eine grössere Beziehung der unterschiedlichen Produktionsorte hergestellt. Liam Gillick wiederum wollte ganz klassischen Buchdruck und hatte in einer Bibliothek neben der Whitechapel Gallery Musterbücher Hugenottischer Textilfabrikanten gefunden – der Familienhintergund der Ringiers ist hugenottisch – und hat diese Muster übertragen auf den Geschäftsbericht und die Charts. Es entstand ein sehr reduzierter Jahresbericht, der aber mit aussergewöhnlich viel Ornament arbeitete und der Frage von Ornament und Darstellung, aber auch der grundsätzlichen Frage, ob „Kunst“ als Verschönerung missbraucht werden kann, nachging.

DB Clegg & Guttmann realisierten eine provokative „Parodie“ des Geschäftsberichts realiick thematisierte das Druckmedium selbst und die Verbindung von Geschichte Ornametellung, dann gibt es eine Mehrzahlalle jene, die m des Auftragsgebers, also mit Bildern, Zeitung, Bildarchiv, Bildherstellungsprozessen und Repräsentation arbeiteten und schliesslich jene, die sich wie Prince und Smith nicht um die Ausgangslage, also den Auftrag, kümmerten.

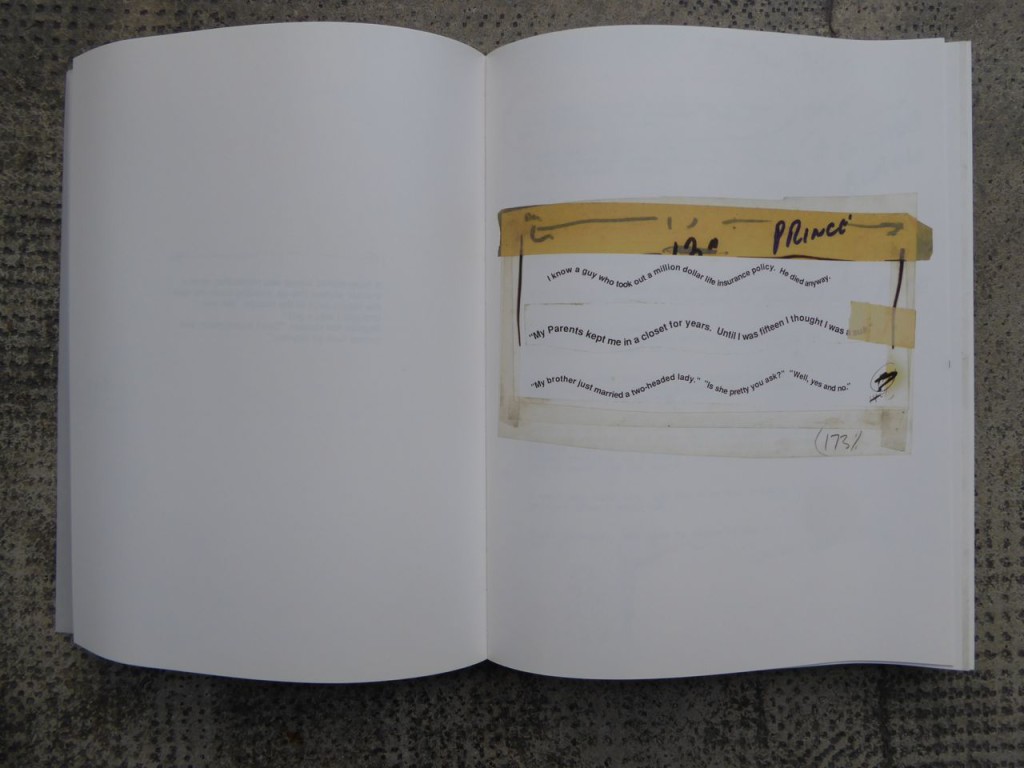

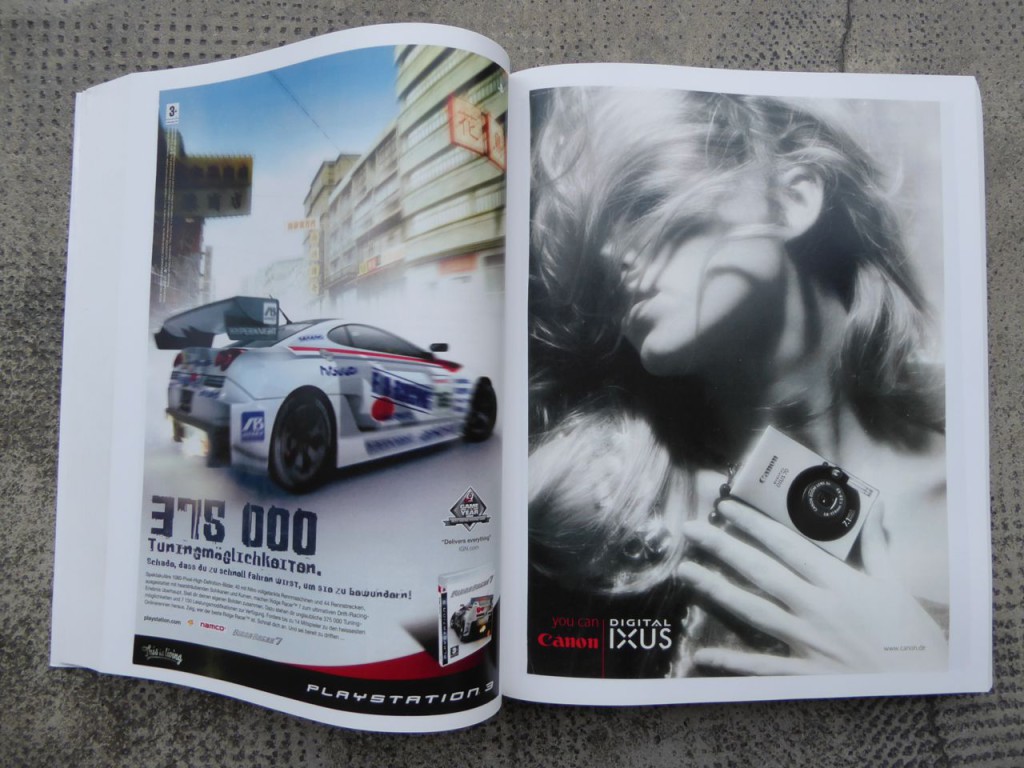

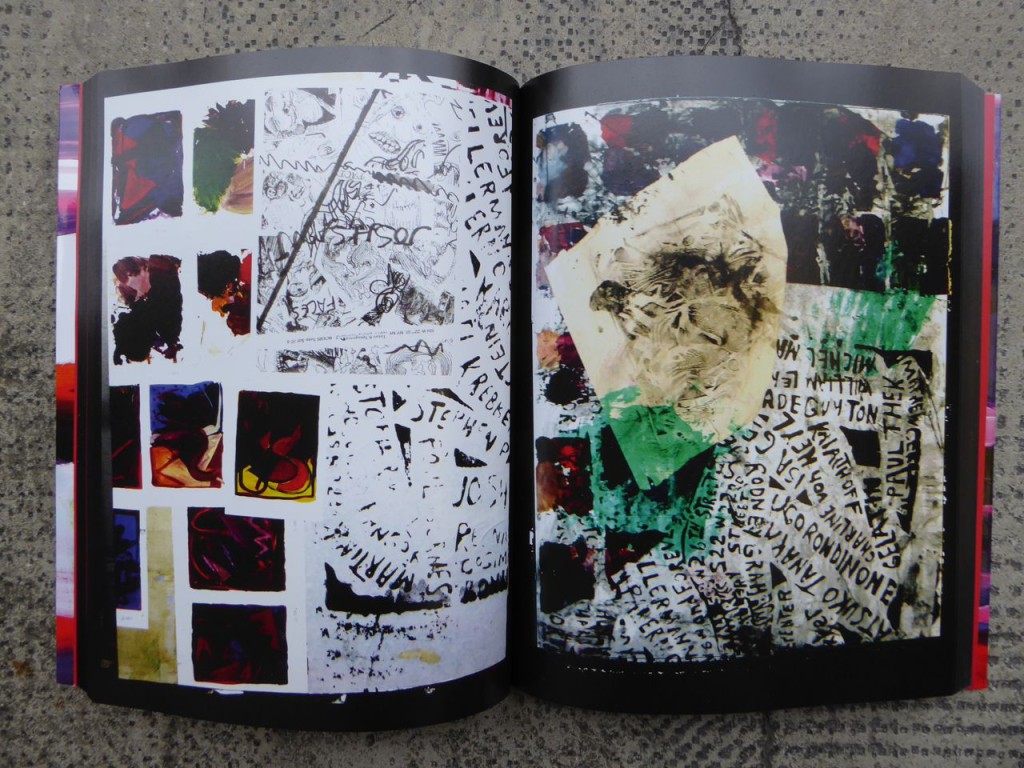

BR Als Künstler musst du ja den Moment der Auftragsarbeit irgendwann ausschalten, ohne ihn jedoch zu vergessen. Die Widersprüchlichkeit lässt sich nicht aufheben. Und der Künstler kann auch nein sagen. Richard Prince zum Beispiel hat keine Werkentscheidung getroffen und auch keine Idee für den Geschäftsbericht selbst entwickelt, sondern einen Stapel seiner Zeichnungen und Notizblätter geschickt, alles unveröffentliches Material, das an Manuskripte und Korrekturfahnen erinnert und eben so auch mit der Medientätigkeit der Firma ein Spiel betreibt trieb („Vveröffentlichen die unfertige Seiten…“), mit der Aufforderung, eine Reihenfolge selbst festzulegen und den Bericht zu intergrieren. Für den Bericht von Peter Fischli und David Weiss stimmte zum Glück der Zeitpunkt der Anfrage, weil es sie diese Arbeit mit den hunderten von Anzeigen machen wollten und diese gut damit zur vermeintlichen „Auftragslage“ passte – aber es war natürlich vor allem eine eigenständige Arbeit, die wie viele der ArbeitenWerke der beiden Künstler um die enzyklopädische Erfassung von Alltag und Welt kreisen.

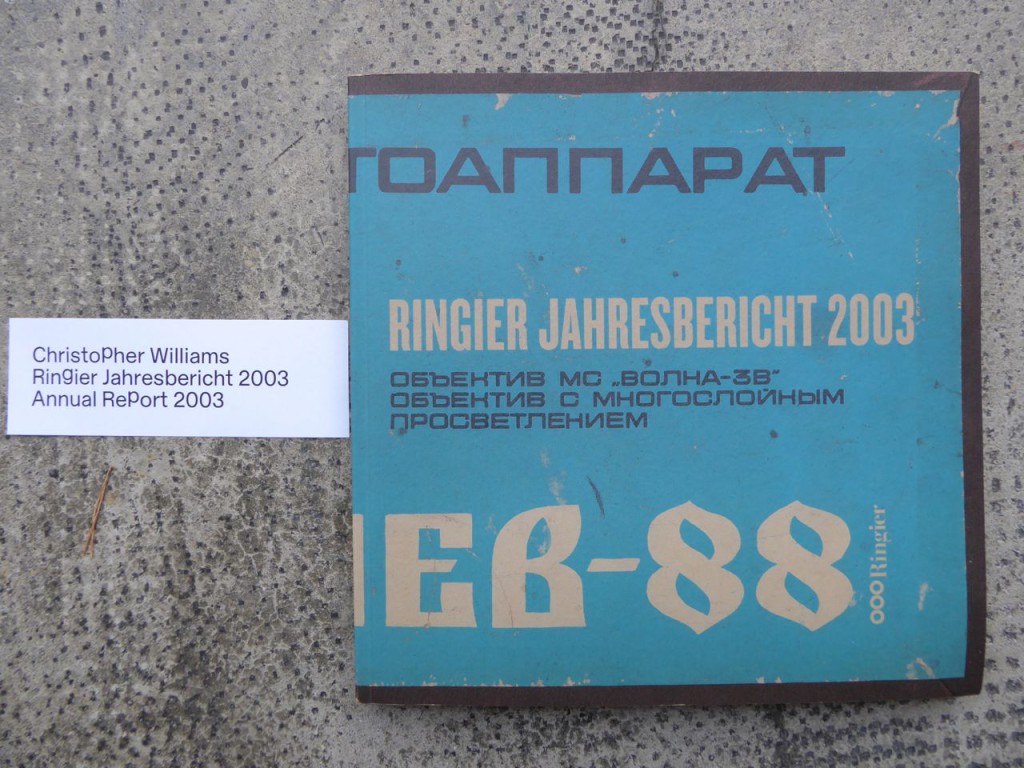

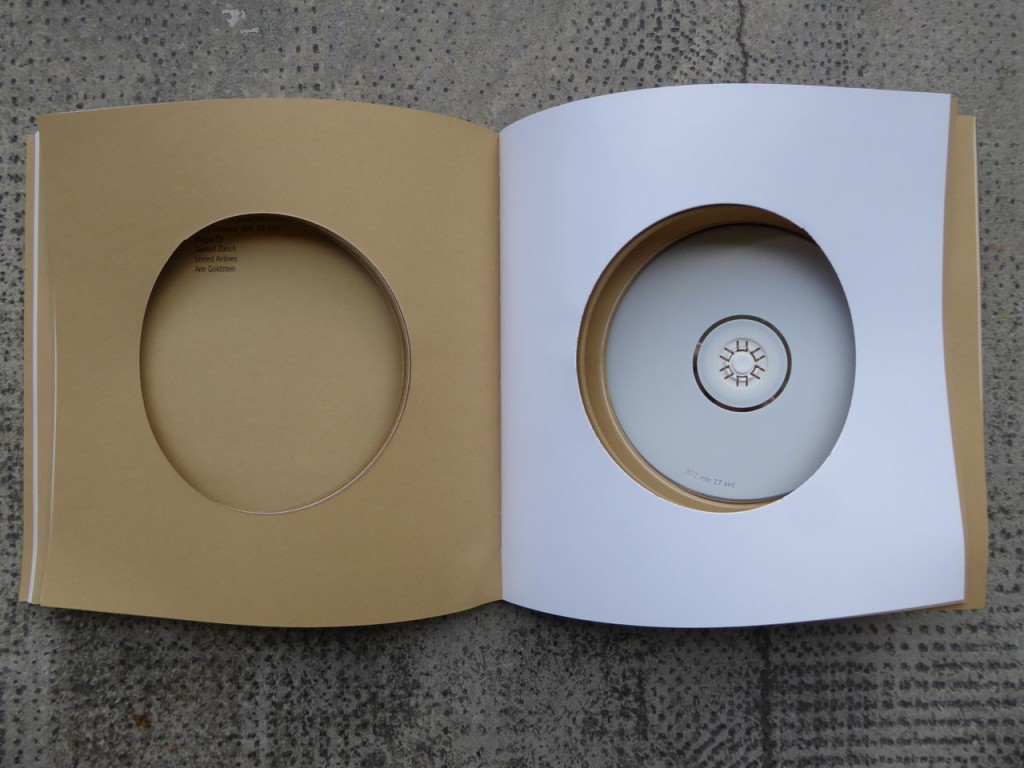

DB Was sich wiederum perfekt mit dem Medienunternehmen traf, das vom Alltag und dessen Brüchen und Erhöhungen lebt. Christopher Williams hat für „seinen“ Jahresbericht sozusagen das Medienunternehmen besetzt und gleichzeitig von seiner Arbeit abgesetzt. Es fängt schon damit an, dass beide gleich viel Seiten bekommen, dass den Seiten mit dem Jahresbericht seine leeren Seiten gegenn. Dazu kommt die eiliegende DVD, eine Kochsendung, wie sie Ringier produziert, jedoch ungeschnitten, also in voller Länge von mehreren Stunden. Williams folgte damit dem Wunsch des Auftragsgebers nach Transparenz und sachlicher Berichterstattung, lieshn aber implodieren, indem er auf real time schaltete, was jedes Geschäft zert. Es reichte, dass er den Blickwinkel leicht verschob und eine neue Form von Wahrhaftigkeit herstellte, die gleichzeitig abslegen sie alle Widersprüche offen dar, ohne sie aufzulösen, abzuschleifen oder zu kaschieren.

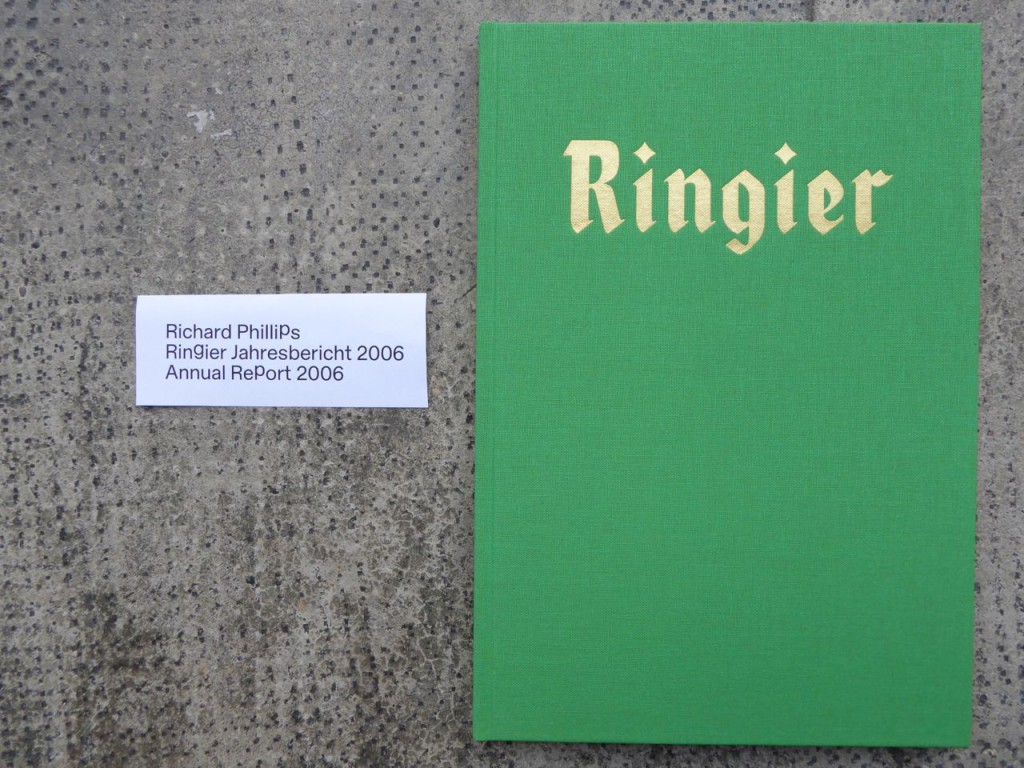

BR Die Gefahr besteht natürlich immer, dass über die Jahre eine Gewohnheit entsteht, es gefällig, seicht oder allzu „hübsch“ wird, dass Künstlerinnen und Künstler diesen wohlgemerkt freiwilligen Geschäftsbericht gestalten, die Firma veröffentlicht ihre Zahlen ja nicht aus Pflicht, sondern aus einer ethischen Haltung. Für den Bericht 2006 hat dann aum Glück Richard Phillips nochmals alles aufgewirbelt. Er hat es nochmals zur Frage gemacht, wie weit die Firma bereit ist, mit der Darstellung ihrer Identität auch in riskante Bereiche zu gehen – denn das ist ja ein Bericht immer auch. Er hat einen Fraktur-Schrifttypus verwendet, den die Nazis anfänglich zur Staatsschrift erhoben, aber dann fallen liessen, als bekannt wurde, dass sie in einer jüdischen Druckerei erfunden worden war. Trotzdem steht die Schrift bis heute für diese Zeit und es ist nicht alltäglich für eine Firma, ihren Erfolgsbericht in diesem Kleid zu verschicken. Man musste Stellung beziehen, es gab intensive und sesionen, man musste auch inhaltlich Stellung für die Zusammenarbeit mit Künstlerinnen und Künstlern beziehen und auch das eigene Selbstverständis formulieren. Was in diesem Fall und für die folgenden Geschäftsberichte eben auch heisst: Ja, wir wollen die alle nötigen Diskussionen.

RINGIER ANNUAL REPORT

by Daniel Bauman. Interview with Beatrix Ruf

MOUSSE – Archive – Issue #19 – 2009

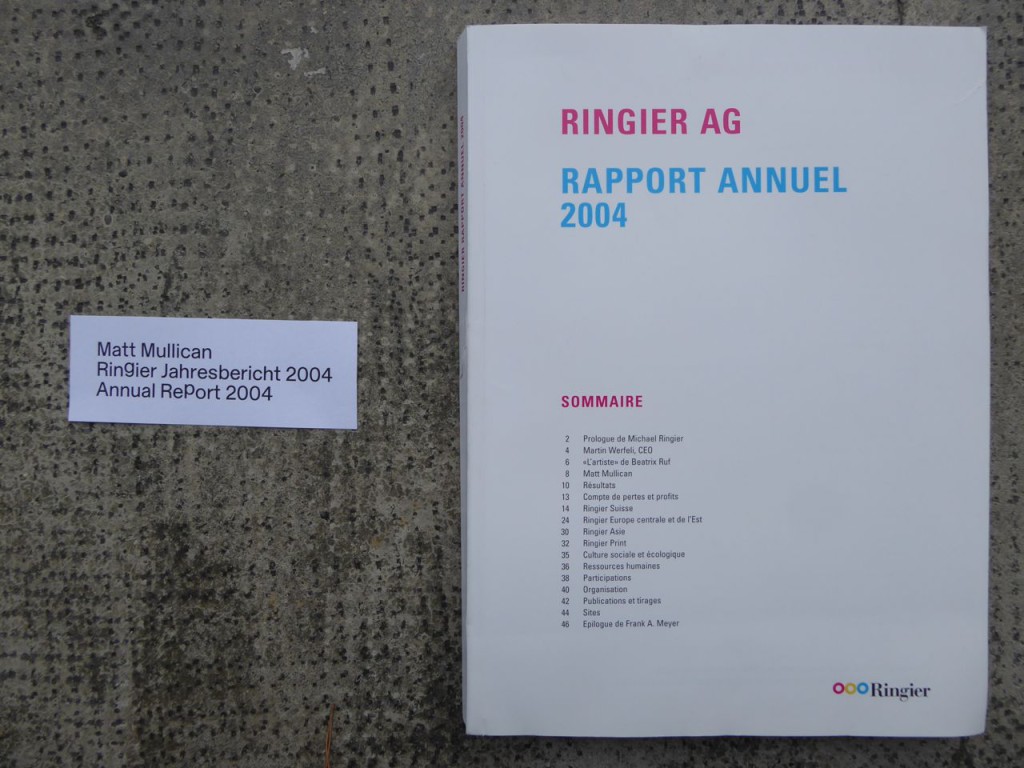

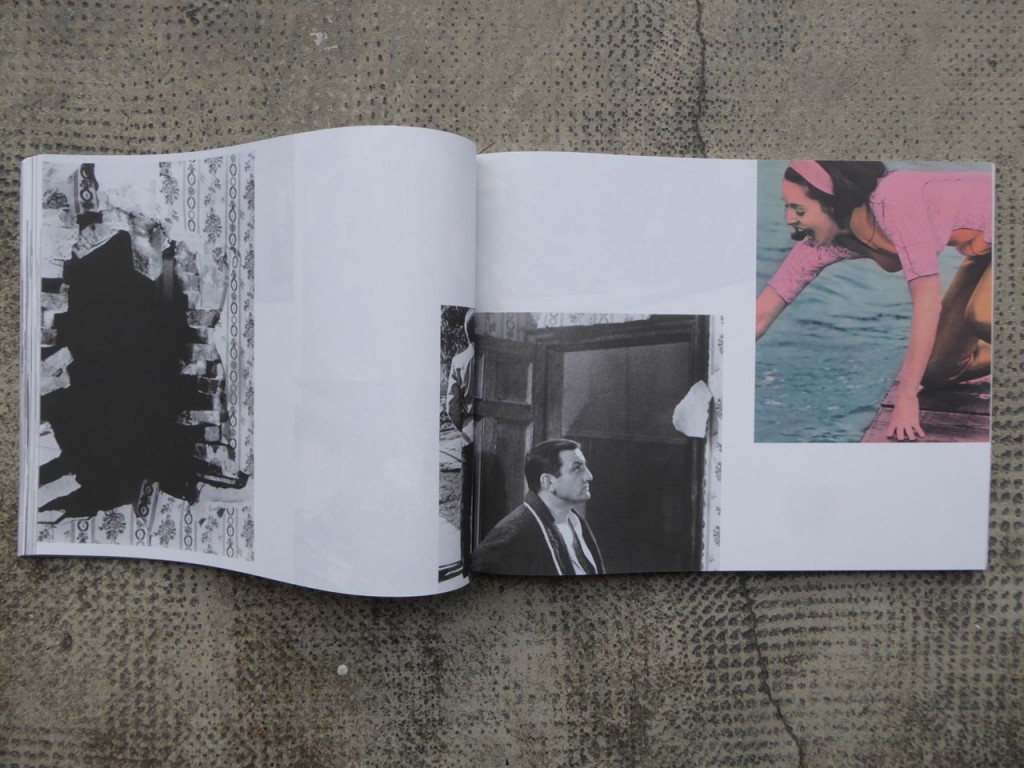

The Ringier Annual Reports, designed by well-known artists since 1997, is one of the most interesting, generous, dubious and aloof publication series of the decade. Every Annual Report from this multinational media enterprise is an artist’s book and advertising brochure as well as a meeting place (or dance floor) for contradictions. The artist’s book as a site for self-empowerment and self-determination here becomes a communication platform for a family business that is not unfamiliar with the dream of selfdetermination. As a result, the free artist meets the free entrepreneur; both are reflected in their wish for independence, while the entrepreneur pays for the other’s freedom and in return gets art, discussion and attention. Clegg & Guttmann made a start in 1997 and were followed by Sylvie Fleury, Christian Philipp Müller, Harald F. Müller, Liam Gillick, Aleksandra Mir, Christopher Williams, Matt Mullican, Richard Prince, Richard Phillips, Peter Fischli/David Weiss and now Josh Smith.

JRP|Ringier

The Ringier Annual Reports appear in three languages in an edition of several thousand copies and are distributed free of charge. Each publication is unique, but all the artists have tried to make use of their licence to be free and thus to include their own instrumentalisation in their calculations. Only Richard Prince seemed not to care a damn about the whole thing, and Josh Smith has gone about it in a similar way. As a publications series the Ringier Annual Reports are a portrait and ballad of co-dependence, both an image and a part of the now decaying decade of finance and its parallel world and, at the same time, in their almost perverse transparency they can also be seen as an alternative to it.

I can think of no publications series that they can be better compared with for ambiguity and hybridism than Psychopathology and Pictorial Expression. An International Iconographical Collection. This was brought out between 1963 and 1977 by the Swiss pharmaceutics group Sandoz to promote their Neuroleptica Melleril. Each edition was devoted to an outsider artist or to a certain theme (“Children’s Drawings and their Bearing on the Doctor-patient Relationship”) and was composed of a scholarly text from cultural history and ten luxurious illustrative tables. Like the Ringier Annual Reports, Psychopathology and Pictorial Expression appeared in several languages and was also distributed free of charge, in thiscase to doctors and psychiatrists. The series was devoted equally to a humanistic image of mankind and to the urge to maximise profits and reflected the longing of middle-class capitalism to reconcile the two spheres. At the same time it was a contribution to the discussion about the borderline between health and sickness, which was then being reformulated in analogy to the concept of art.

In contrast to Ringier, however, Sandoz did not want to create a profile for itself in art. For Ringier is not only an internationally active media enterprise, but also by now an important actor in the art world. In the course of the last few years Michael Ringier has built up a significant collection of contemporary art for his firm. In this he has been advised by Beatrix Ruf, the Director of the Kunsthalle Zürich, which in turn curates the annual reports. In addition, in 2004 Ringier went into business with the small publishing firm of Verlag JRP (Just Ready to be Published), founded in Geneva in 1994, and, with the help of its founder Lionel Bovier has developed into one of the leading and most reputed publishers of contemporary art. Lastly, in 2006 the art magazine Monopol was added to the range. At the beginning of May I had a meeting with Beatrix Ruf in Zurich to learn more about the Ringier Annual Reports.

Beatrix Ruf: Until now it has been a project in process. The idea came to us in New York, in the gallery of Colin de Land, where we saw works of Clegg & Guttmann in 1996. For a year Michael Ringier and I talked about the direction the collection should take. He and his wife Ellen already have a splendid collection of avant-garde works on paper from around 1900. Now he wanted quite particularly to build up a collection for the firm, on a very long-term basis and with the ideas constantly being discussed for the firm’s collection about how art could be integrated into the everyday life and concerns of the firm, what this might mean for the employees etc. To some extent I have a critical attitude to this collection, because I think that no corners should be cut or compromises made. Quite spontaneously we asked ourselves whether these very annual reports might not be an opportunity to integrate a certain kind of artistic practice, to initiate a special situation for the business report, which would of course also become a special situation for the employees and the artists. The first Annual Report with Clegg & Guttman was a disaster, to put it mildly. They work with photography and they got confused with the photographers normally hired for annual reports. When Clegg & Guttman came they all thought that they were again coming for their annual photographs. But these two set up extreme scenes with clear prescriptions for clothing, dark suit, white shirt, red tie, the uniform insignia of authority and power. They lit the scene with an extreme, almost unbearable light, in order to get strong contrasts and to evoke historical paintings. Furthermore, they only portrayed the management level, which was a breach of taboo. There was opposition, but also some very interesting discussions. Clegg & Guttman didn’t fully explain their methods, but on the other hand in this first project it was not clear to what extent the artists could really intervene in the corporate image of the firm.

Daniel Baumann: And with the next Annual Report?

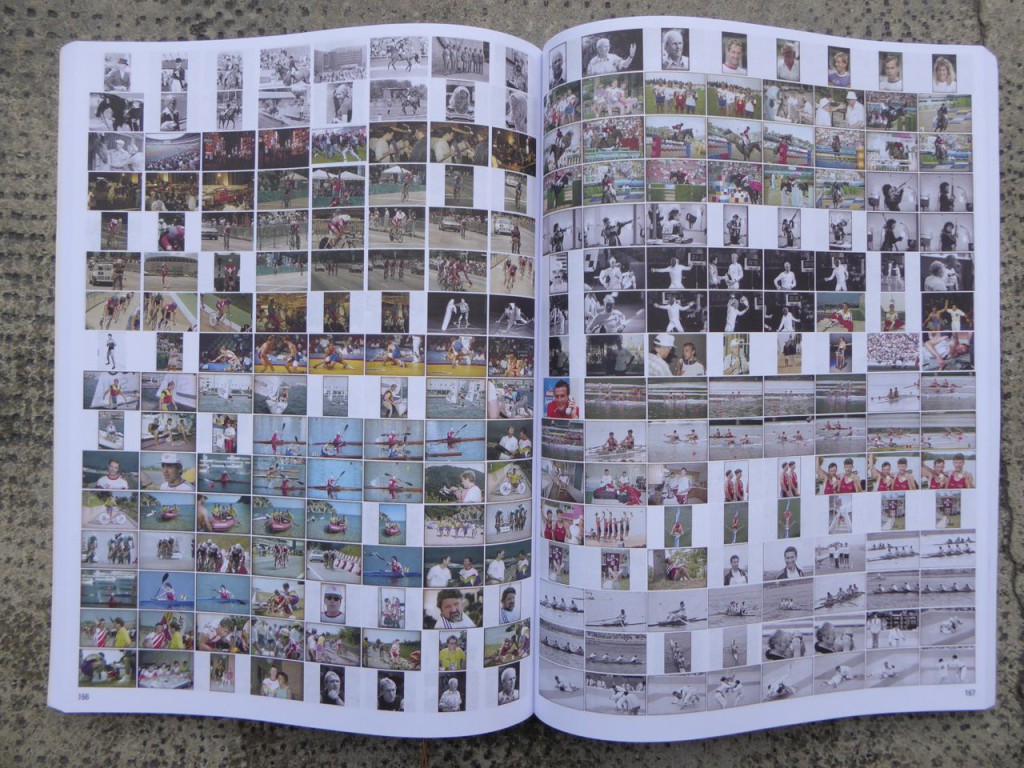

By then the carte blanche was fully established: there were no longer any prescriptions regarding format, design and contents, except of course that the figures and reports had to be included and legible. Many artists worked in and with the company archive, such as Aleksandra Mir and also Matt Mullican, who catalogued the digital image archive of the firm with a system he developed personally: he designed a sort of cosmology of the image archive and developed a calculation model to find out how many pictures would have to be shown per page in order to get a kind of basic illumination of the digital archive in the analogue printed form. Christian Philipp Müller, on the other hand, travelled for a whole year at the firm’s expense and visited all the sites where the firm is active. He played the role of a fictitious investigative “journalist” and created a kind of hybrid between national portrait, story of discovery and travel guide. That led to a lot of discussion because he reproduced clichés and countries thought they were presented too “typically” and, in their eyes, incorrectly, and yet he also produced great commitment and a broader relationship between the various production sites. Liam Gillick, for his part, wanted totally classical book print and found a library of Huguenot pattern from textile manufacturers next to Whitechapel Gallery – the background of the Ringier family is Huguenot – and he had these patterns carried over to the business report and the charts. The result was a much reduced annual report, but it worked with an unusually large amount of ornamentation and pursued the question of ornament and representation as well as the fundamental question as to whether “art” can be misused as beautification.

Clegg & Guttmann recognised a provocative “parody” of the business report; Gillick focused on the print medium itself and the association of ornament and presentation; and then there were all those who worked with the patron’s own medium, namely images, newspapers, image archive, image production processes and representation and finally those like Prince and Smith, who took no notice of the initial situation, the commission itself.

As an artist you have to switch off the fact of commissioned work, but without forgetting it. The contradiction cannot be resolved. And the artist cannot say no. Richard Prince, for example, made no decision on the work and developed no idea for the annual report himself, but sent a pile of his drawings and sketches, all of it unpublished material, that reminds one of manuscripts and galley proofs and in that way played a game with the media activity of the firm (“Publish the unfinished sheets…”), with an order to determine a sequence for themselves and integrate the report into it. For the report of Peter Fischli and David Weiss, the timing of the inquiry was fortunate because they wanted to make this work with hundreds of advertisements and adapted these to the alleged “commission” – but of course it was mainly an independent work which, like many of the works of these two artists, circled around the encyclopaedic assembly of everyday things and the world.

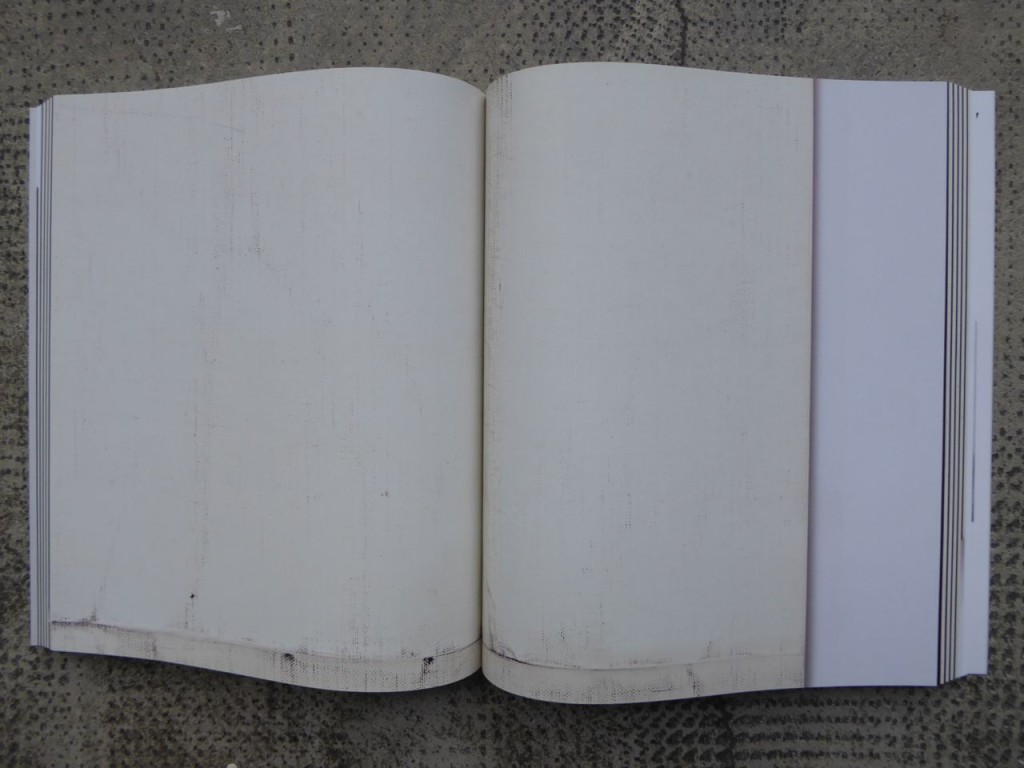

Which in turn fitted in perfectly with the media enterprise, which lives from the everyday and its interruptions and intensifications. For “his” annual report, Christopher Williams more or less occupied the media enterprise and at the same time used it for his work. It begins with both sides getting the same number of pages, the pages with the annual report facing his empty pages. With that comes the attached DVD, a cooking programme of the kind produced by Ringier, but uncut, in other words at the full length of several hours. In this way Williams responds to the patron’s wish for transparency, but lets it implode by switching to real time, which destroys any business. It was enough for him to shift the angle of vision slightly and create a new form of verity, which was also absurd. In this way the contradictions are left exposed, without being resolved, reduced or masked.

Of course there is always a danger that a habit will be established over the years, so that it is pleasing, shallow or all too “pretty” that artists design this – be it noted – voluntary report. The firm publishes its figures not because it has to but from an ethical point of view. For the 2006 report Richard Phillips, thank goodness, stirred everything up again. He again questioned just how willing the firm is to carry the presentation of its identity even into risky regions – for a report is always that as well. He used a Fraktur typeface, which the Nazis originally gave the status of a state printing form, but they dropped it later when it became known that it had been invented in a Jewish printing house. In spite of that, the typeface still stands for that time and it is not an everyday event for a firm to send out a report of its success dressed up like this. A statement had to be made, there were intensive debates, a statement also had to be made about the cooperation with artists and the firm’s own selfimage had to be formulated. Which means, in this case and also for all the following annual reports: yes indeed, we want to have all the necessary debates and discussions.

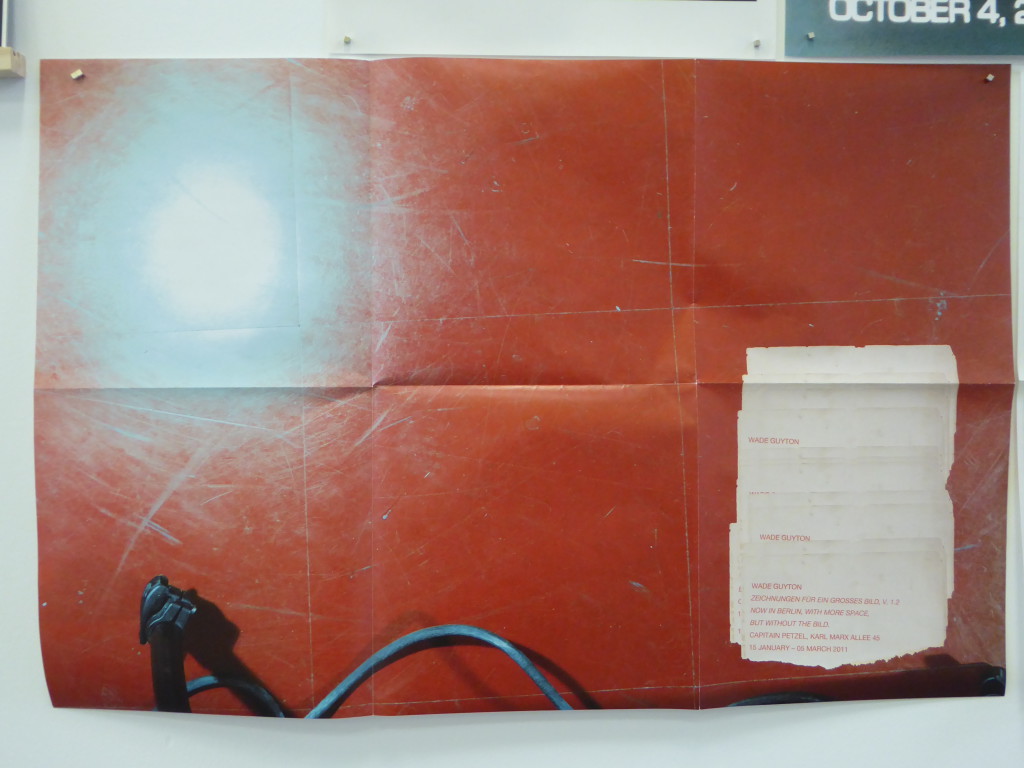

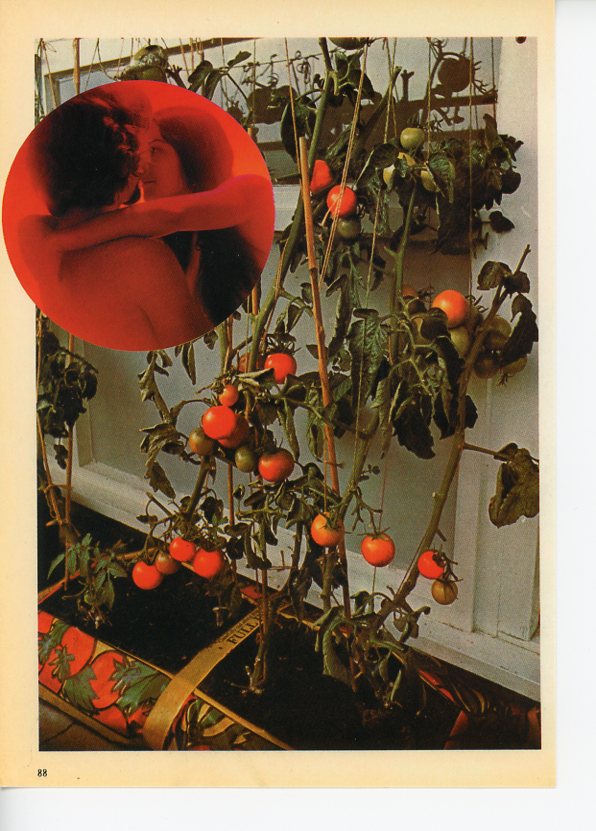

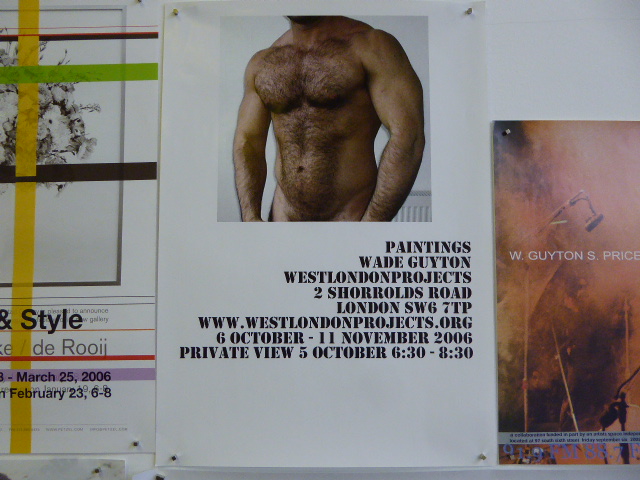

Wade Guyton

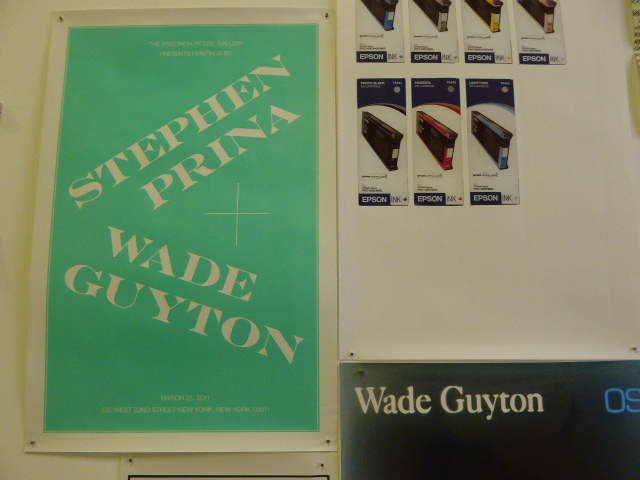

Anonymous user comment: “I didn’t see the show. But I love the card! Reminds me of something – it takes me somewhere – I would magnet this to my fridge.”

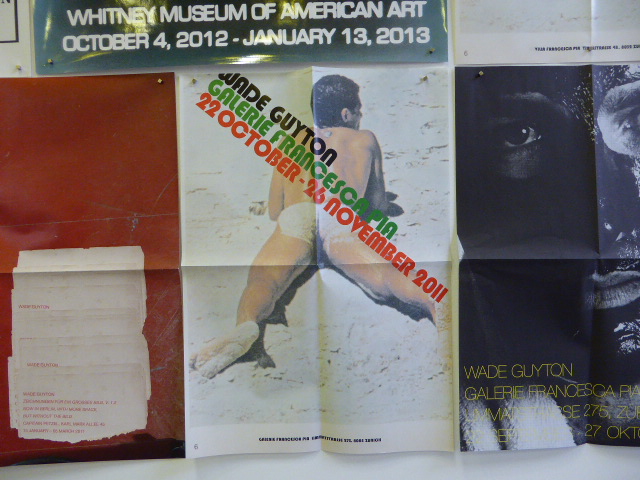

Wade Guyton’s first exhibition at Galerie Francesca Pia in 2005, still in Bern. See images here (scroll all the way down).

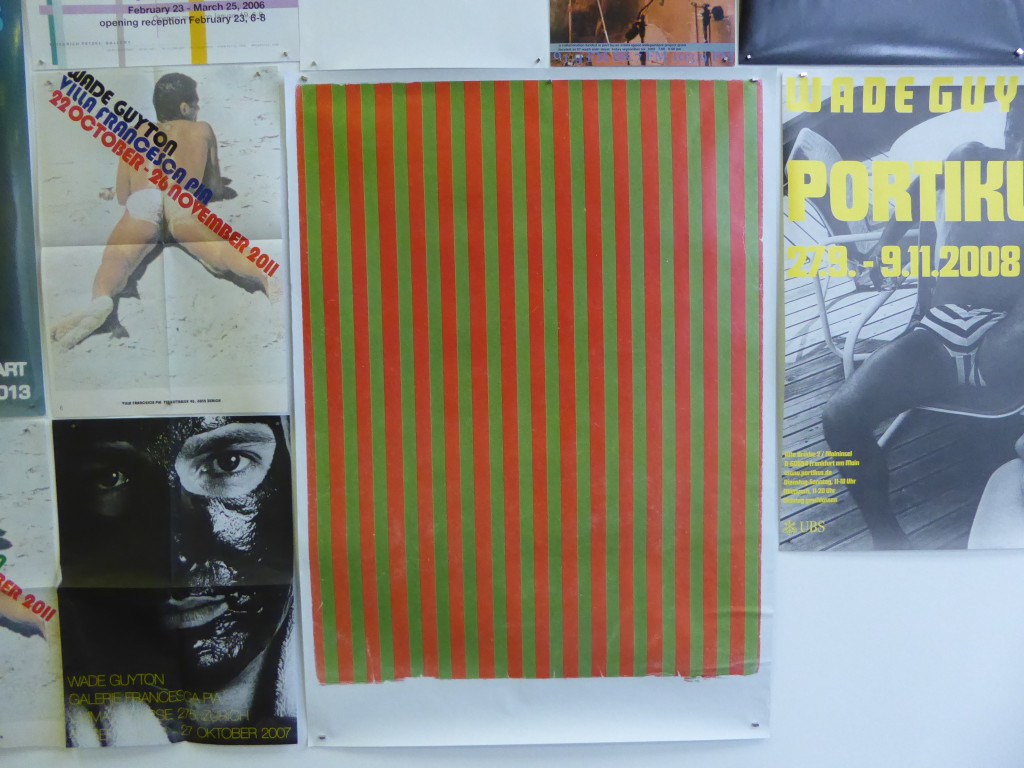

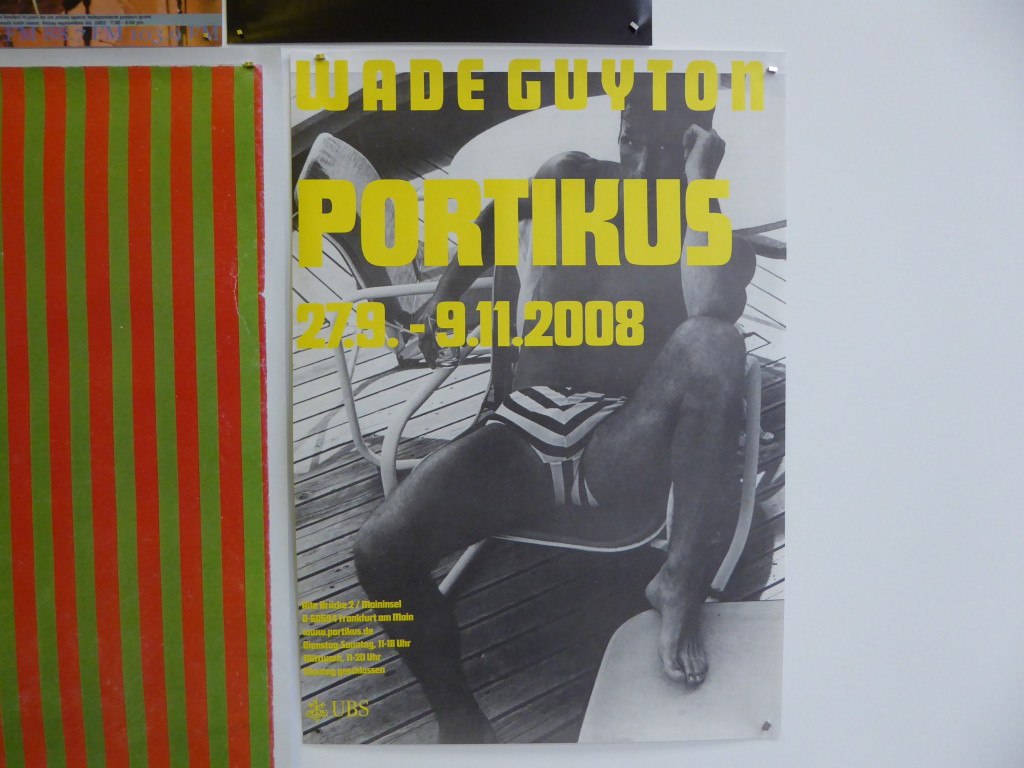

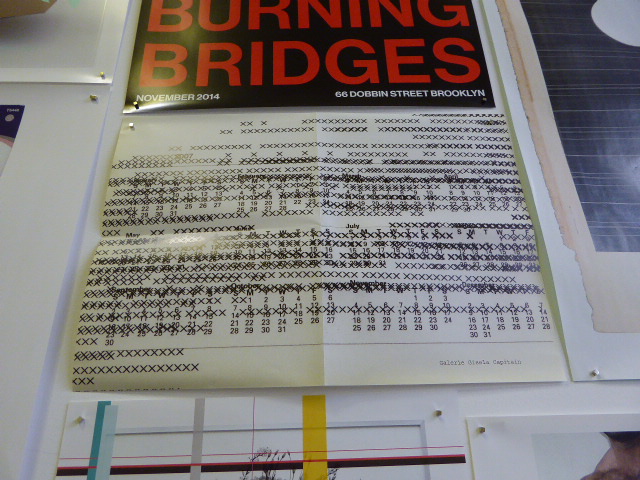

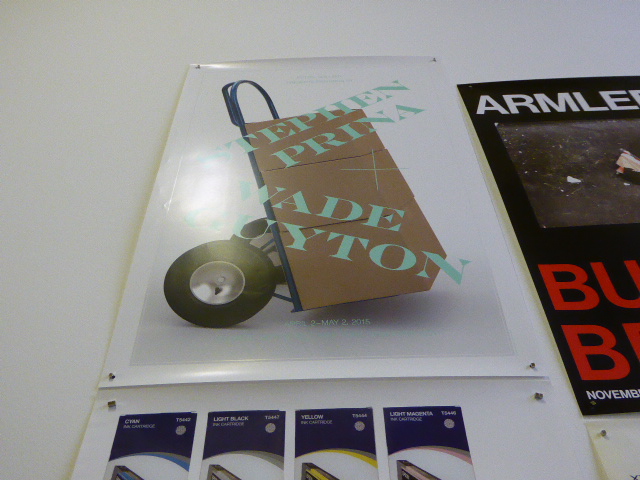

Wade Guyton Posters

follow

follow