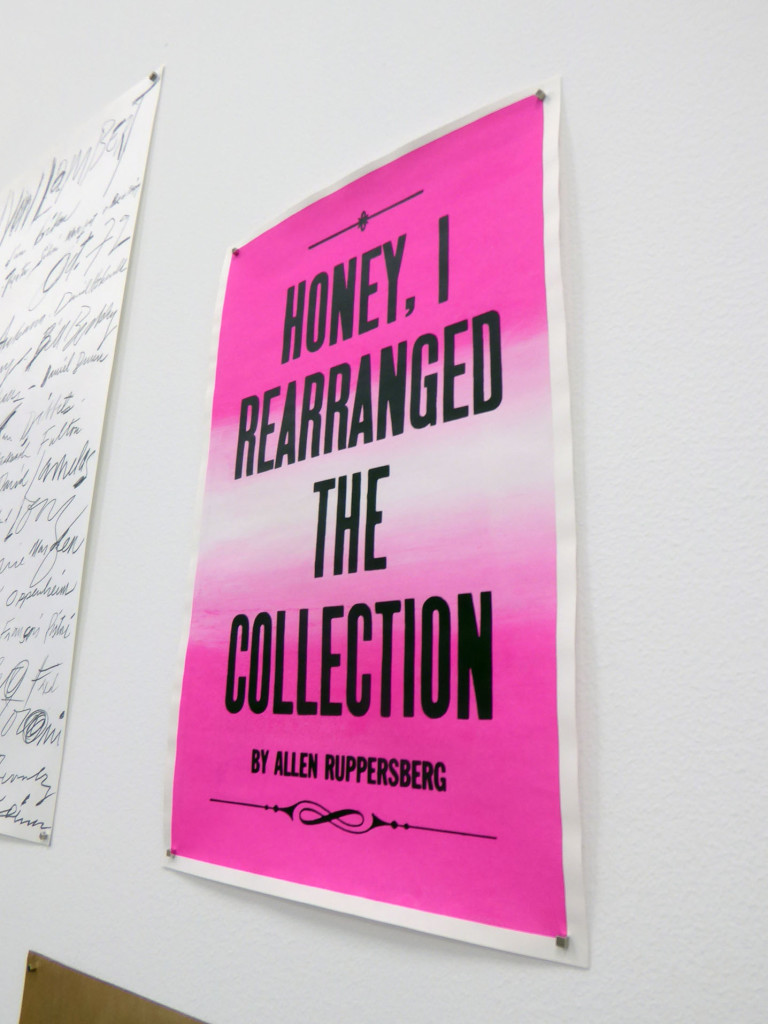

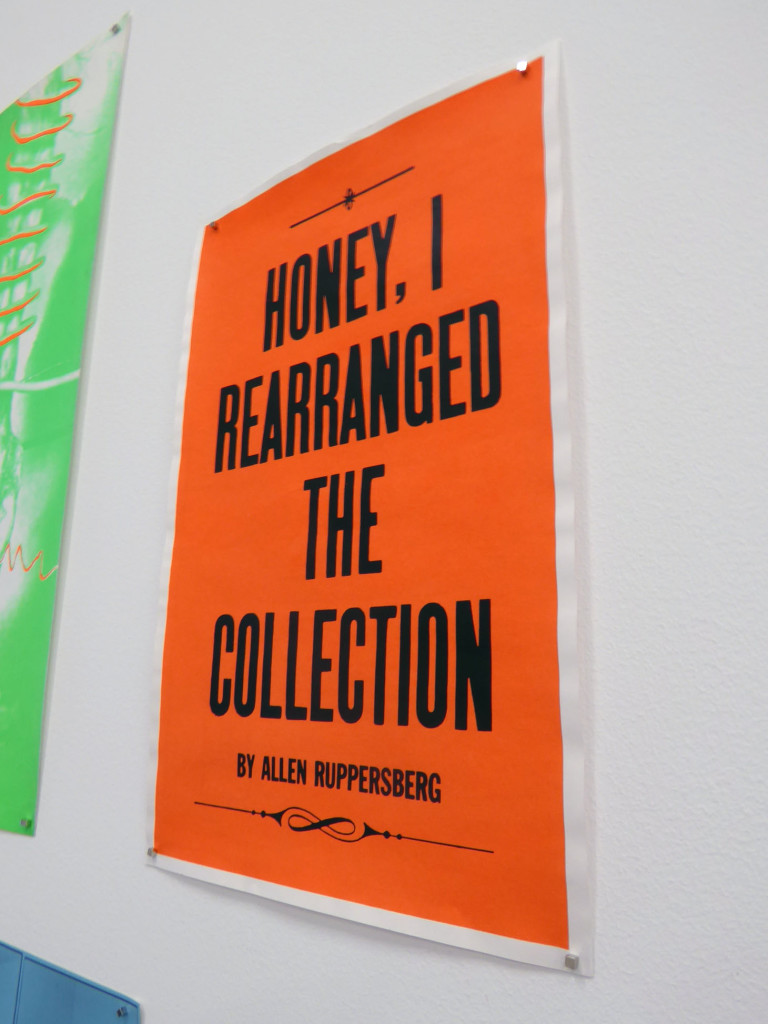

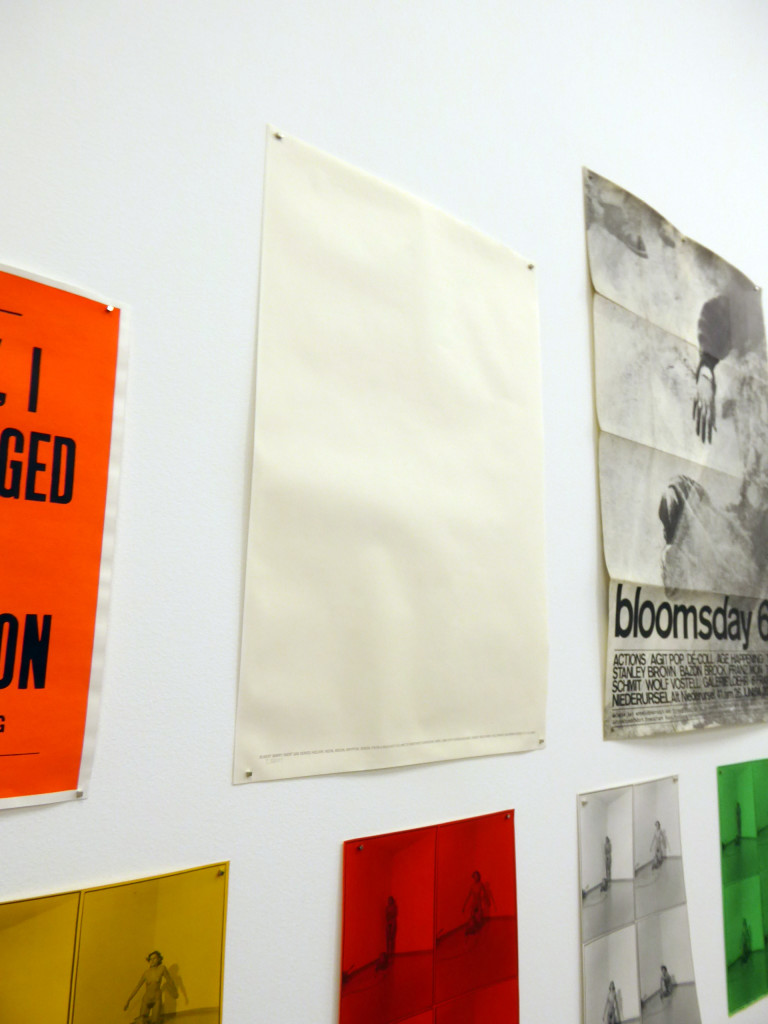

Allen Ruppersberg and Lionel Bovier about the posters

Allen Ruppersberg’s Honey, I Rearranged The Collection

Multifunctional 3

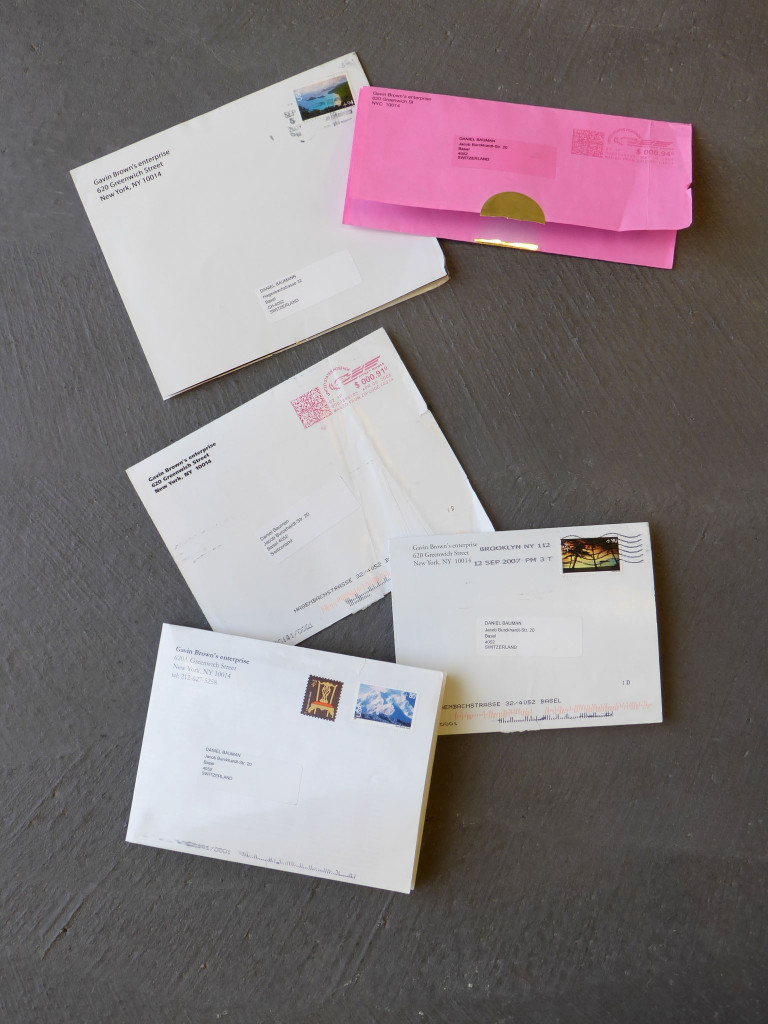

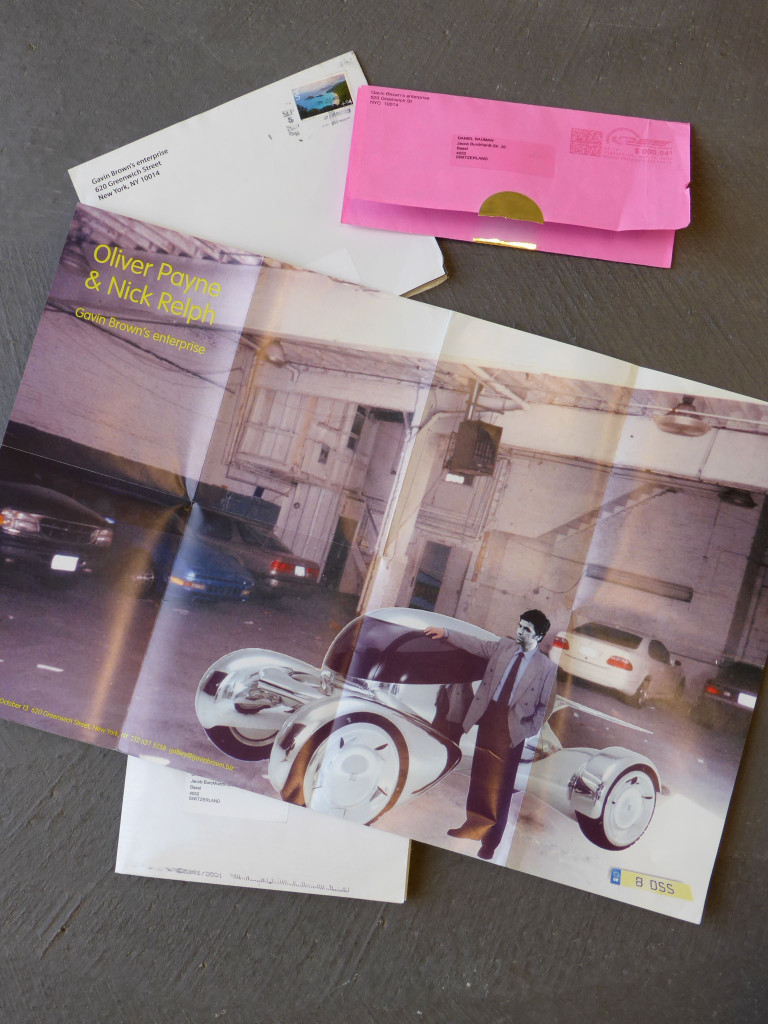

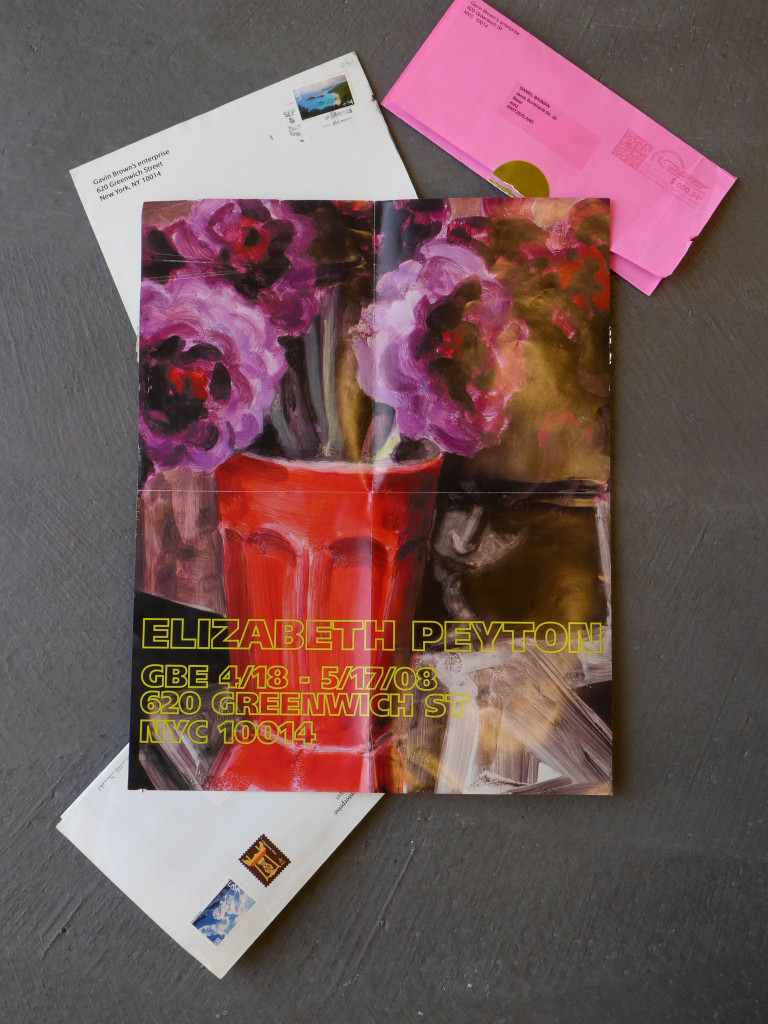

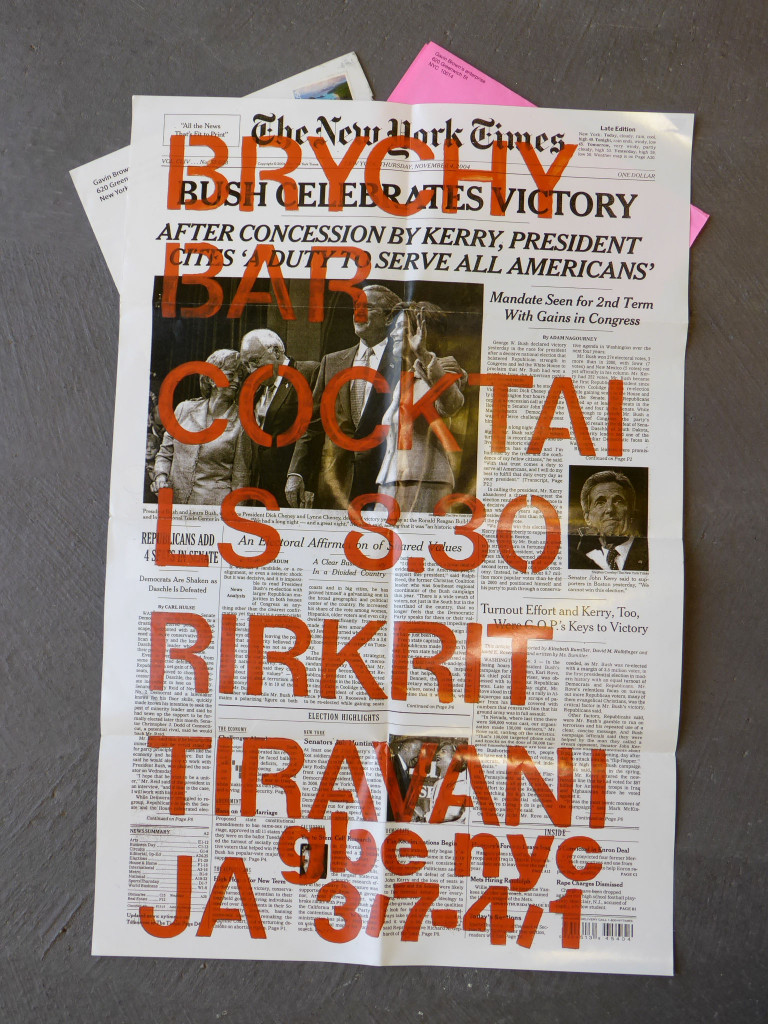

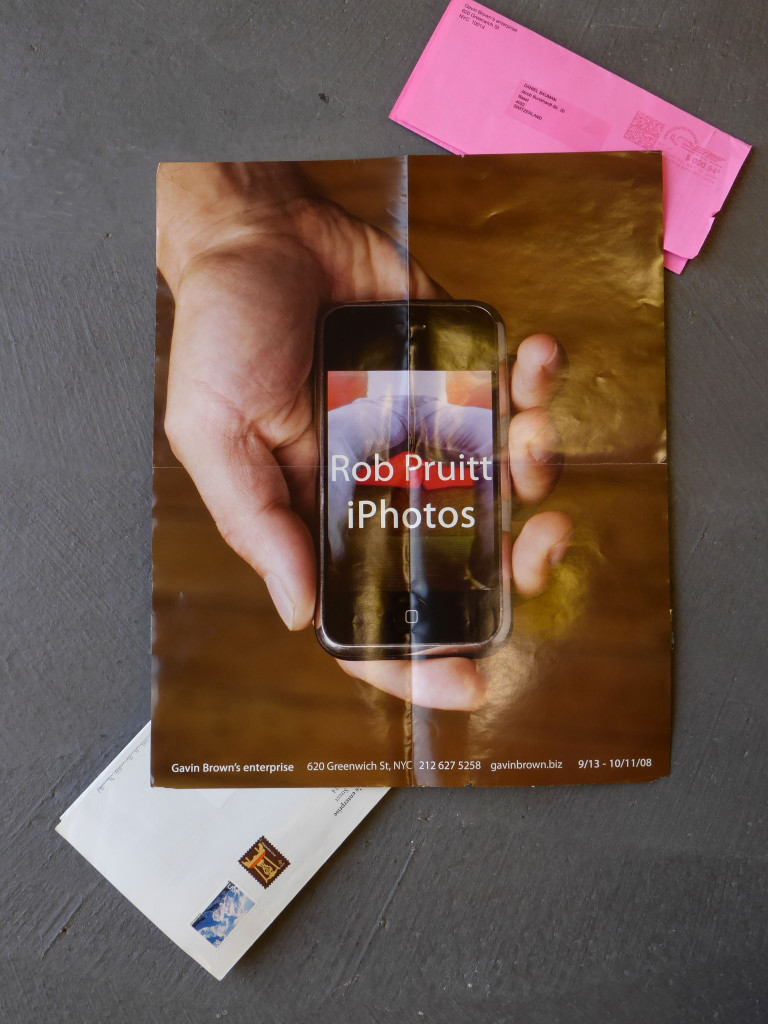

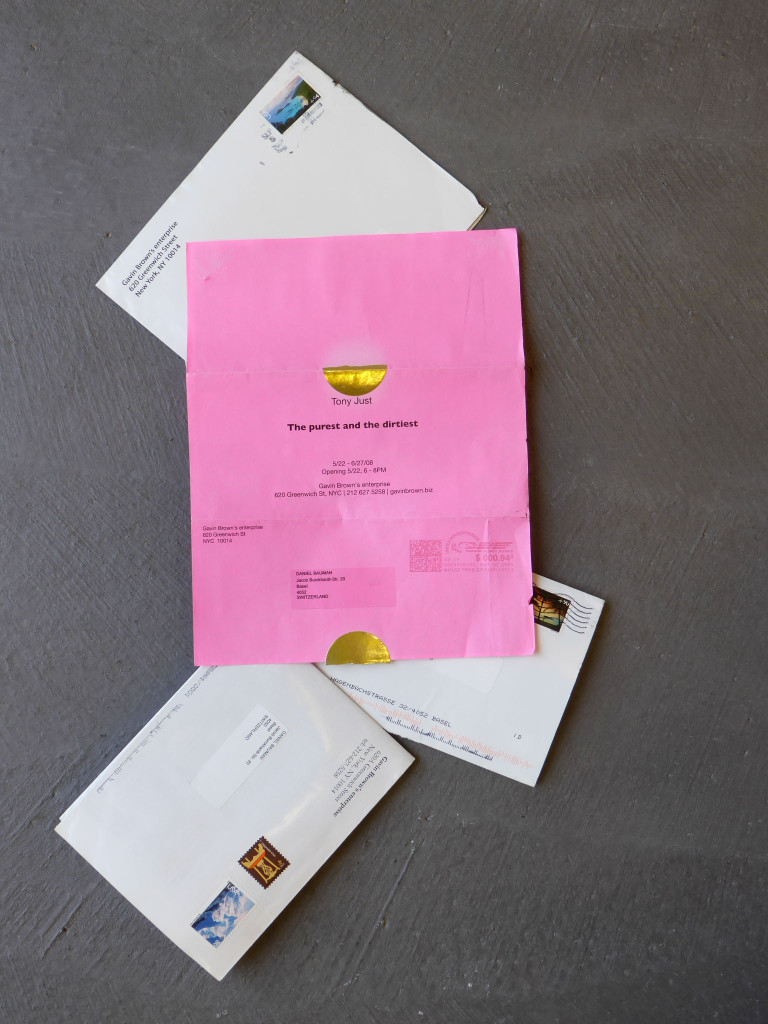

Here are some more posters which also function as their own envelope.

Related posts:

Multifunctional

Multifunctional 2

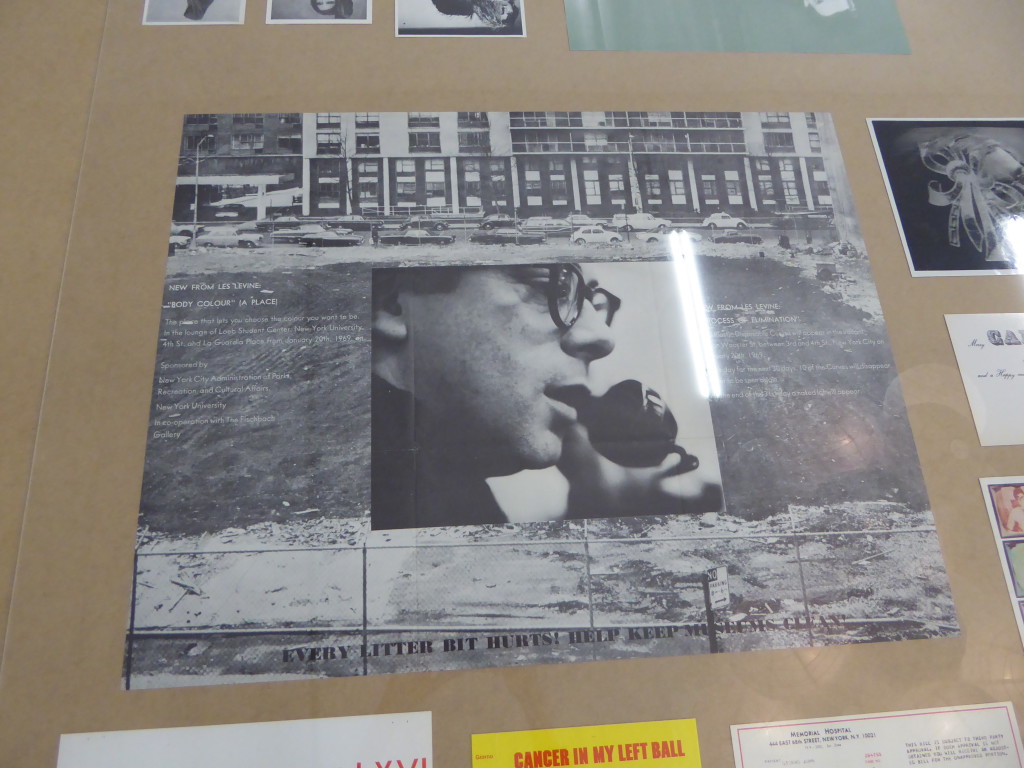

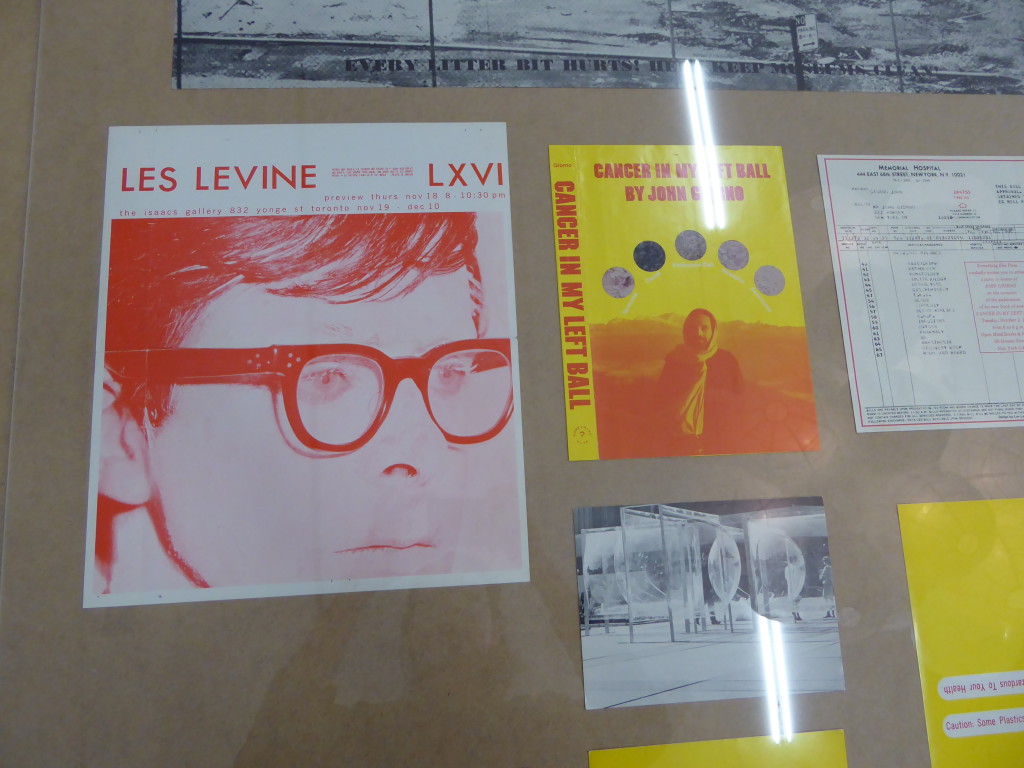

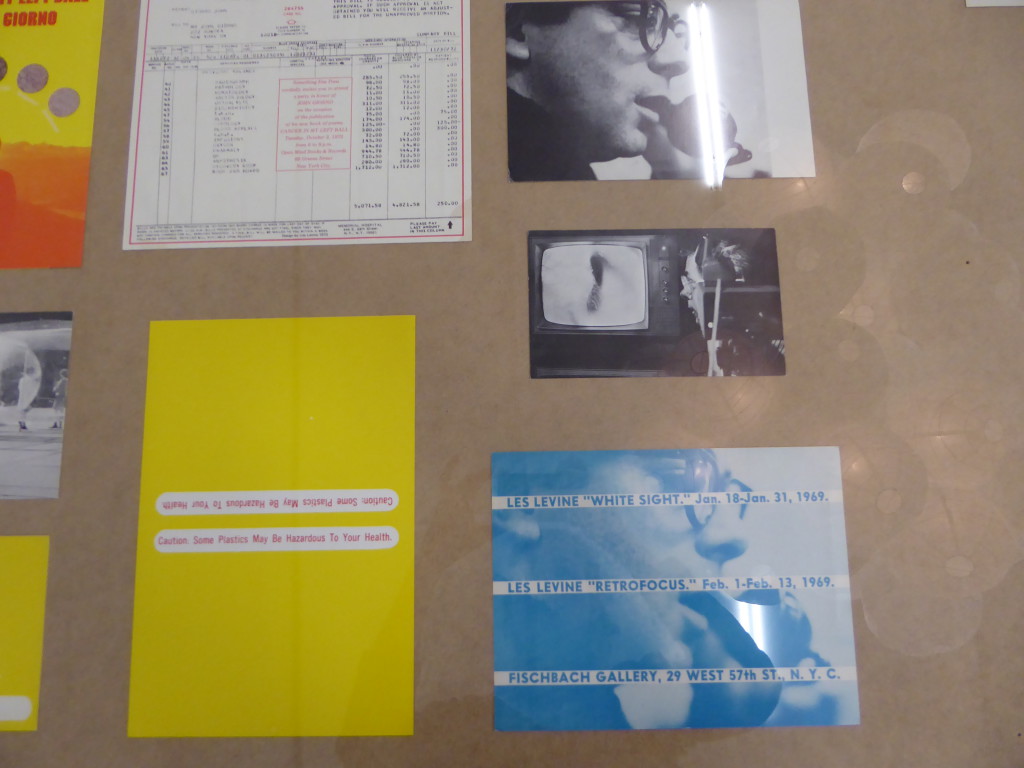

Les Levine

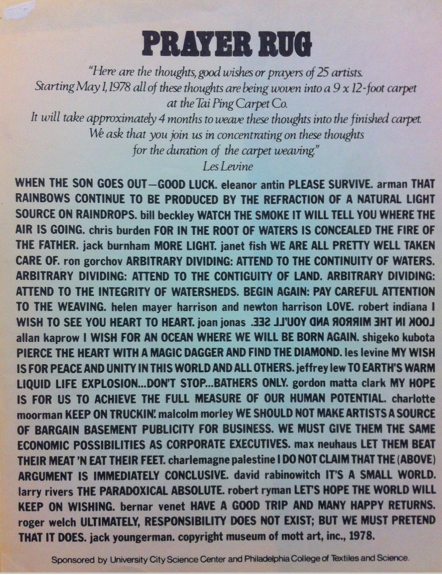

Les Levine: Poster Prayer Rug 1978

Das Poster von Les Levine (1935*) erscheint als Werkankündigung (?) der tatsächlichen Arbeit Prayer Rug[1]. Für seine Arbeit fragt er diverse Künstlerkollegen nach kurzen Gebeten, Wünschen oder Weisheiten, die er anschliessend in einen Teppich weben lassen will. Es entsteht daraus eine Sammlung an 25 Sprüchen von 26 verschiedenen Künstlern[2], die vorläufig auf dem Plakat abgedruckt werden. Auch Les Levine selbst fügt der Sammlung eine Anweisung bei: PIERCE THE HEART WITH A MAGIC DAGGER AND FIND THE DIAMOND. Levine ordnet die Gebete, wie es scheint aleatorisch, und fügt sie in einen fortlaufenden Fliesstext. Während die Gebete selbst in Grossbuchstaben gesetzt sind, sind die Künstlernamen jeweils davon unterschieden in Kleinbuchstaben zu lesen.

Als der Teppich am 1. Mai 1978 in der renommierten Tai Ping Carpet Co. Fabrik in Hong Kong in Auftrag gegeben wurde, lässt Les Levine mehrere Exemplare dieses 58 x 74 cm grossen Plakates drucken. Diese werden bloss für die Zeit der Teppichproduktion an verschiedenen Orten in New York aufgehängt. In der Überschrift des Plakates erklärt Les Levine die Hintergründe des Werkes und übergibt dem Betrachtenden eine Aufgabe „[…] concentrating on these thoughts fort he duration oft he carpet weaving“. Durch die Ankündigung des Werks anhand des Plakates lädt Les Levine den Produktionsprozess zudem mit Spannung auf, da der Teppich während dieser Zeit der Konzentration durch die Betrachter materiell noch nicht vorhanden ist.

Die Inspiration für das Werk beschreibt Les Levine wie folgt: „The idea comes from the ancient Oriental prayer rugs which were used for periods of quiet contemplation and meditation.“ Les Levine hat sich bei den Proportionen zudem an klassischen Gebetsteppichen des Islams orientiert. Im Gegensatz dazu seien aber in Levines Fall die Betenden in keinen spezifischen religiösen Kontext eingebunden. Sie bewegen sich vielmehr in einem weltlichen Gebiet der guten Wünsche und Hoffnungen. Weder Religion, noch Spiritualität nehmen hier also eine zentrale Rolle ein. Vielmehr beschäftigt sich die Arbeit während ihrer Herstellung – und damit in diametralem Gegensatz zum kostbaren Kunsthandwerk, zu dem das Werk am Ende wird – mit den Massenmedien und der Kommunikation. Im Press Release des Museum of Mott Art, – eine Art imaginäre Institution, die von Levine selbst 1970 gegründet wurde – wird nämlich das Weben des Teppichs mit dem Weben von Information durch moderne Medientechnik gleichgesetzt: „In this work the weaving of the rug represents the weaving of information by mass-media. Prayer Rug considers the effects of repeated messages on belief systems.“ Les Levine sieht in den heutigen Fernsehwerbungen die einzigen effektiven Gebete unserer Zeit. Er unterscheidet also nicht zwischen vormodernen Formen der Religion und modernen, scheinbar säkularisierten Techniken des Kommerzes und der dort eingesetzten Medientechniken.

Er stellt mit seiner Arbeit die Praktizierung der heutigen Religion in Frage, der die Kraft in seinen Augen verloren gegangen ist. Er erhofft sich, dass die prayers der Künstler eine ähnliche Glaubenskraft ausstrahlen können, wie sie die Fernsehwerbungen in seiner Gegenwart erreichen.[3]

UZH, Übung: They Printed It! Wanda Seiler

[1] dt.: Gebetsteppich.

[2] Der eine Gedanke wird vom verheirateten Künstlerduo Helen Mayer Harrison und Newton zusammen formuliert.

[3] vgl. Umbrella (1979): Interantional News: New York Byline. New Hopes. Aminoff, Judith. Vol 2, No 2. https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/umbrella/article/viewFile/479/448 (20.12.15).

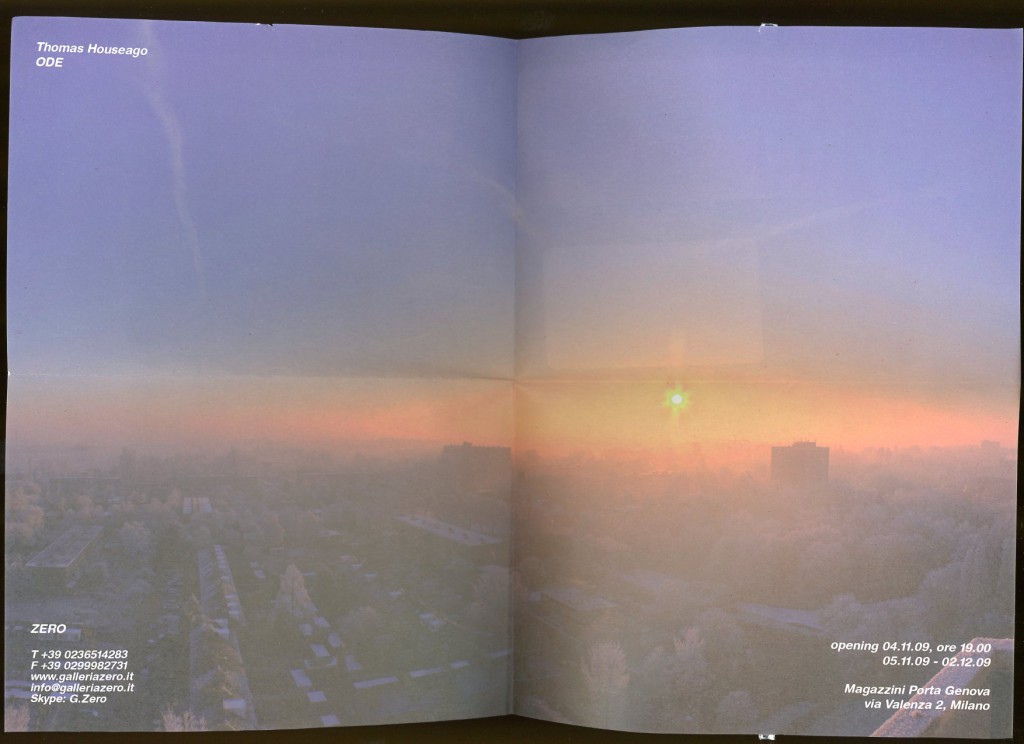

Thomas Hauseago: Ode

User Beitrag: “Schön und einfach. Die Rückseite hat ihre eigene Geschichte und macht den Druck zum Inhalt.” Sven

Evidence

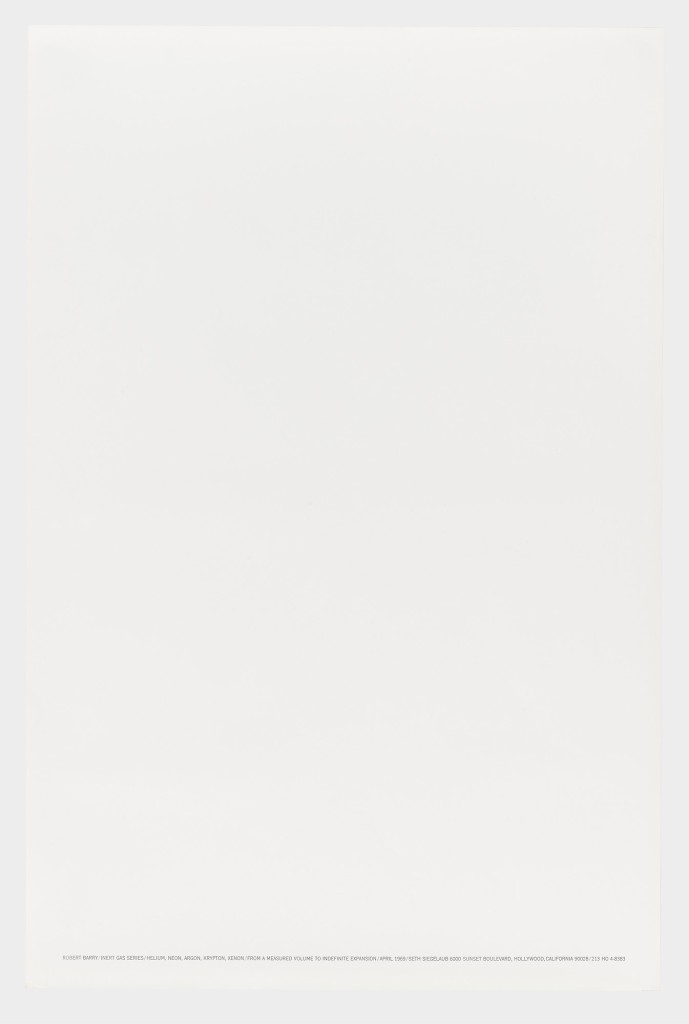

Testing the limits of materiality, Barry produced this poster for an exhibition that had neither a location nor a date. The address is a post-office box, and the telephone number for the gallery is an answering service with a recorded message describing the “work.” The work was the release, by the artist, of five measured volumes of odorless, colorless, noble gasses into the atmosphere in various locations surrounding Los Angeles, where they would diffuse and expand naturally into infinity.

While documentary photographs were taken of the action of the releases, the only physically tangible evidence of the work would remain the poster, published by the New York art dealer Seth Siegelaub, who stated, “He has done something and it’s definitely changing the world, however infinitesimally. He has put something into the world but you just can’t see it or measure it. Something real but imperceptible.”

Sources:

www.moma.org/collection/works/109710

classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/532/flashcards/3747532/png/41-142CE8D58F41C9592F1.png

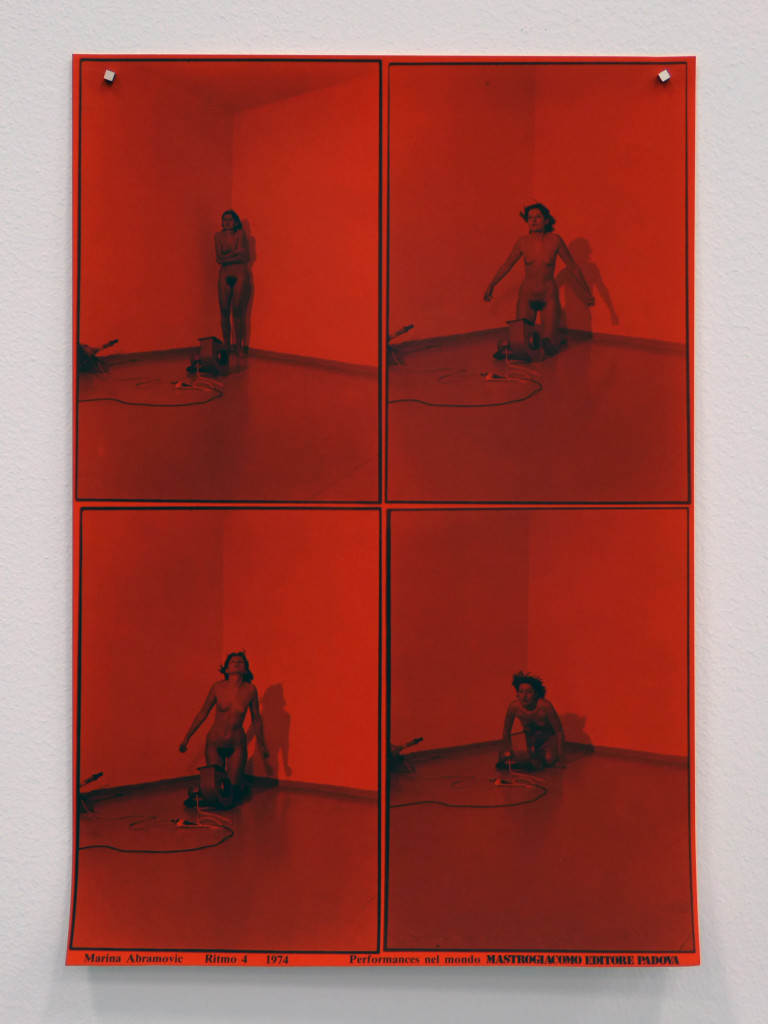

Marina Abramovic

User Beitrag: “Jedes Mal, wenn ich der Künstlerin Abramovic begegne, bin ich fasziniert. Ich verfolge sie siet ihren Anfängen. Ich finde sie sehr mutig und sie ist wichtig für die Kunst. Ich sage bewusst nicht (Frauen)-Kunst.” Beatrice Haupt

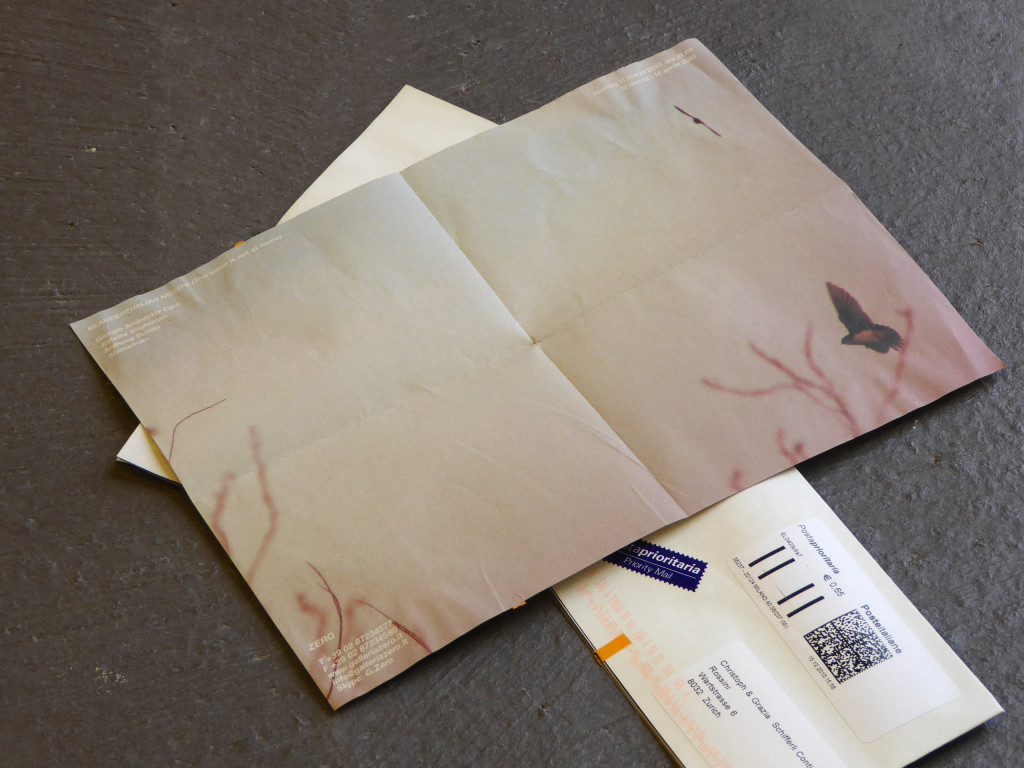

Multifunctional 2

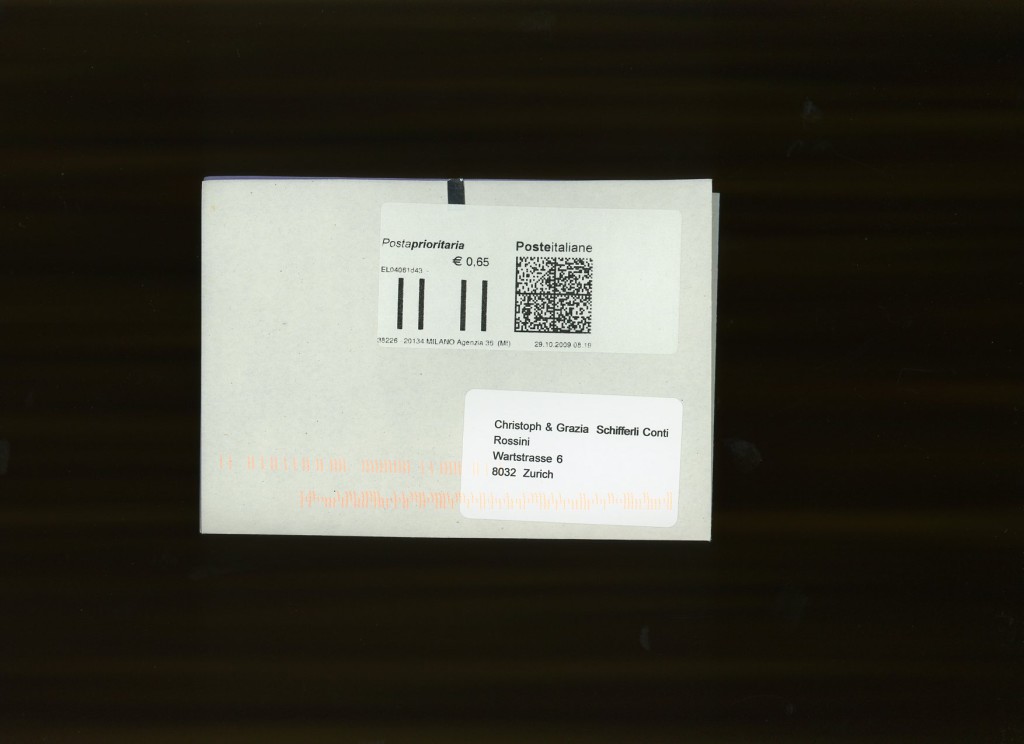

The galeries KARMA INTERNATIONAL and ZERO both created invitation cards / posters which also function as their own envelope.

Marina Abramovic, Ritmo 4, 1974

“Rhythm 4 was performed at the Galleria Diagramma in Milan. In this piece, Abramović kneeled alone and naked in a room with a high-power industrial fan. She approached the fan slowly, attempting to breathe in as much air as possible to push the limits of her lungs. Soon after she lost consciousness.[28]

Abramović’s previous experience in Rhythm 5, when the audience interfered in the performance, led to her devising specific plans so that her loss of consciousness would not interrupt the performance before it was complete. Before the beginning of her performance, Abramović asked the cameraman to focus only on her face, disregarding the fan. This was so the audience would be oblivious to her unconscious state, and therefore unlikely to interfere. Ironically, after several minutes of Abramović’s unconsciousness, the cameraman refused to continue and sent for help.[28] Wikipedia

Point d’ironie: Koo Jeong-A

User comment: “I have chosen an invitation for the exhibition of Koo-Jeong-A (2009)’s work. I found the format and the colours and the blurred shapes intriguing. I had to unfold the document and the surprise and the curiosity remained high (what’s this?). I immediately thought about FRAMING it. I did not know the artist nor the gallery. I find sometimes the invitation for famous artists (eg. Charles Ray, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Isa Genzken, Wolfgang Tillmans etc.) whom I also adore eye-catching, but rather because they produce a feeling of familiarity, like a recognisable friend on meets in the street. But there is less surprise, rather a soft happiness/joy?” Carole Ratsimandresy

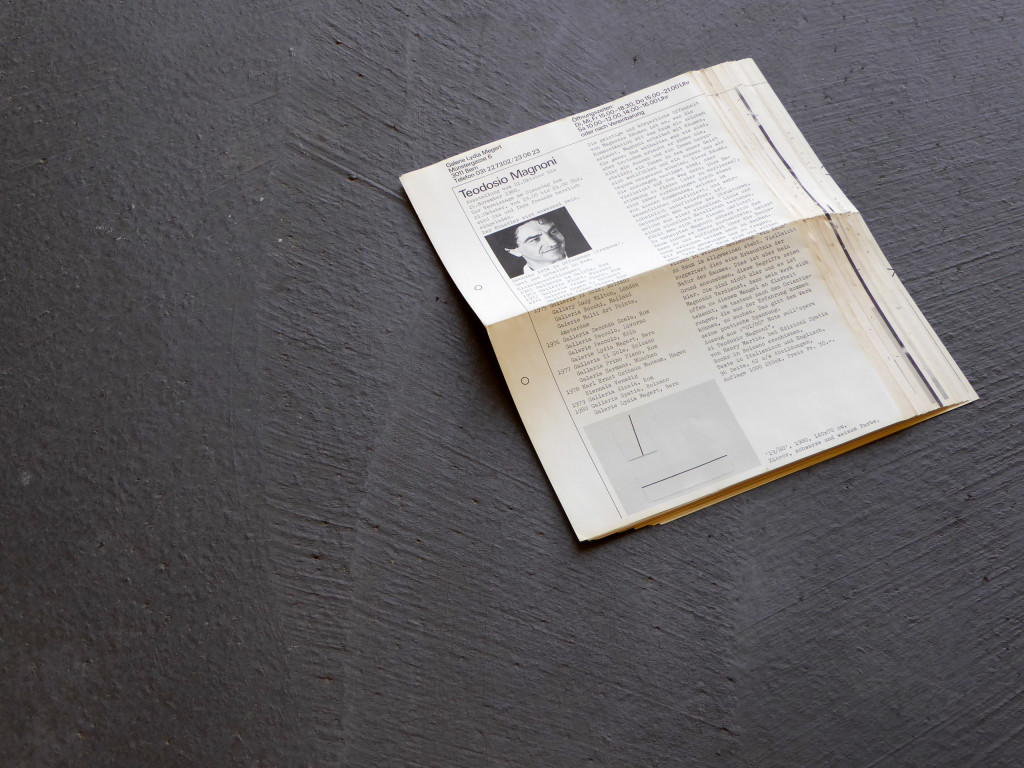

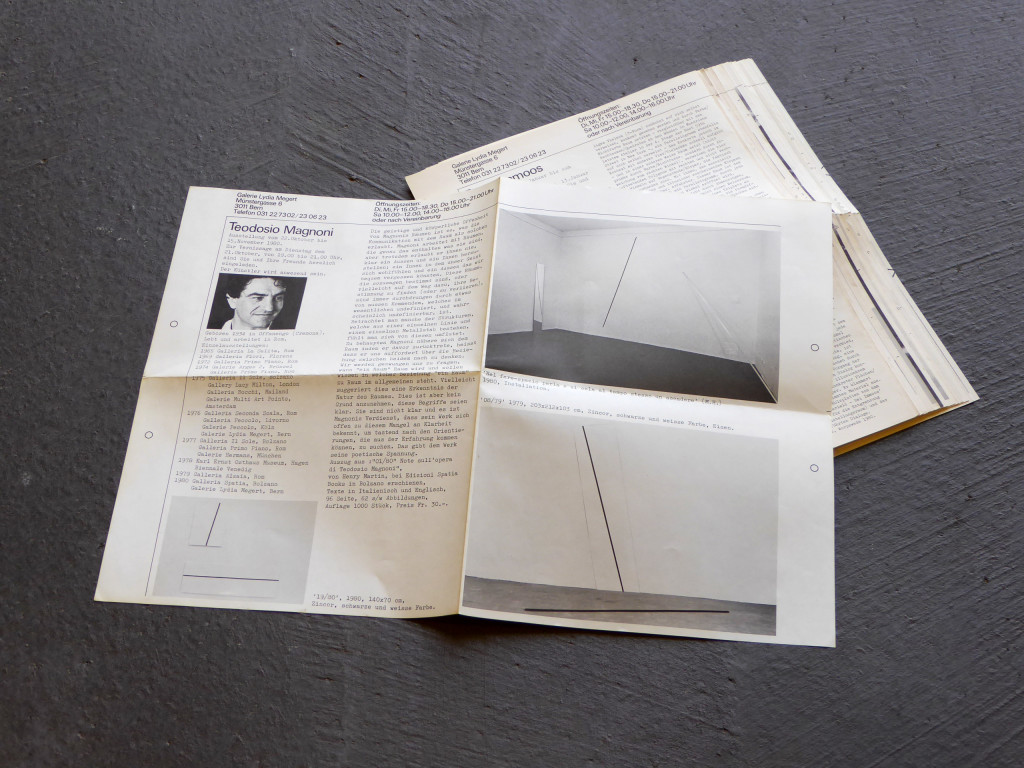

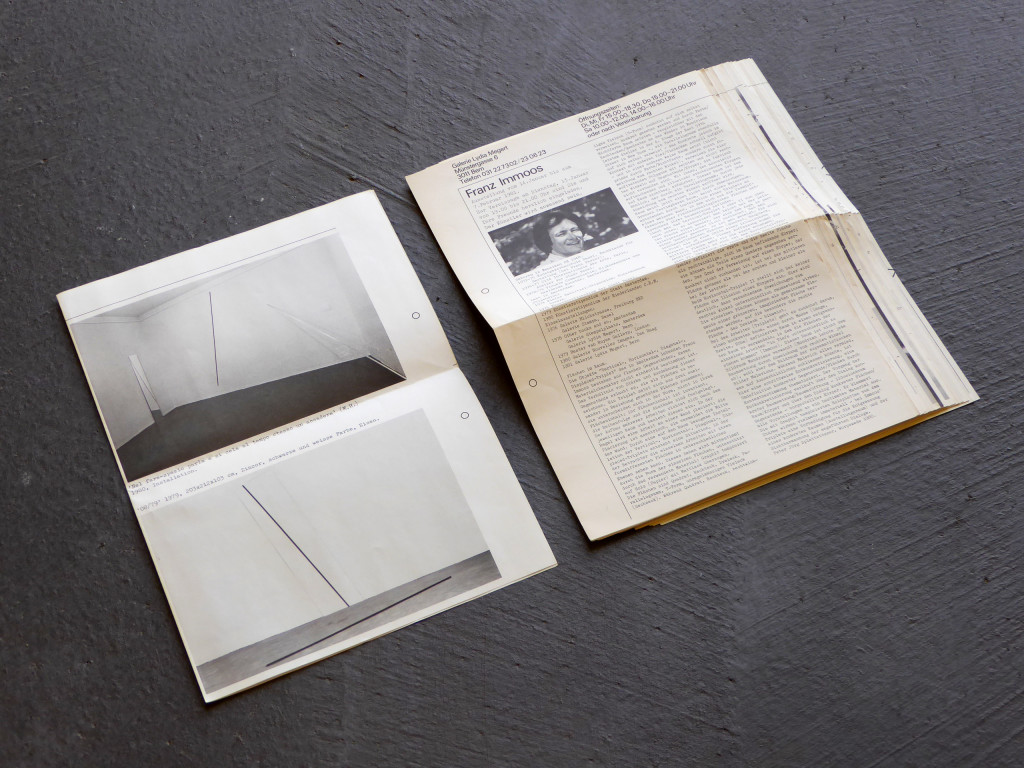

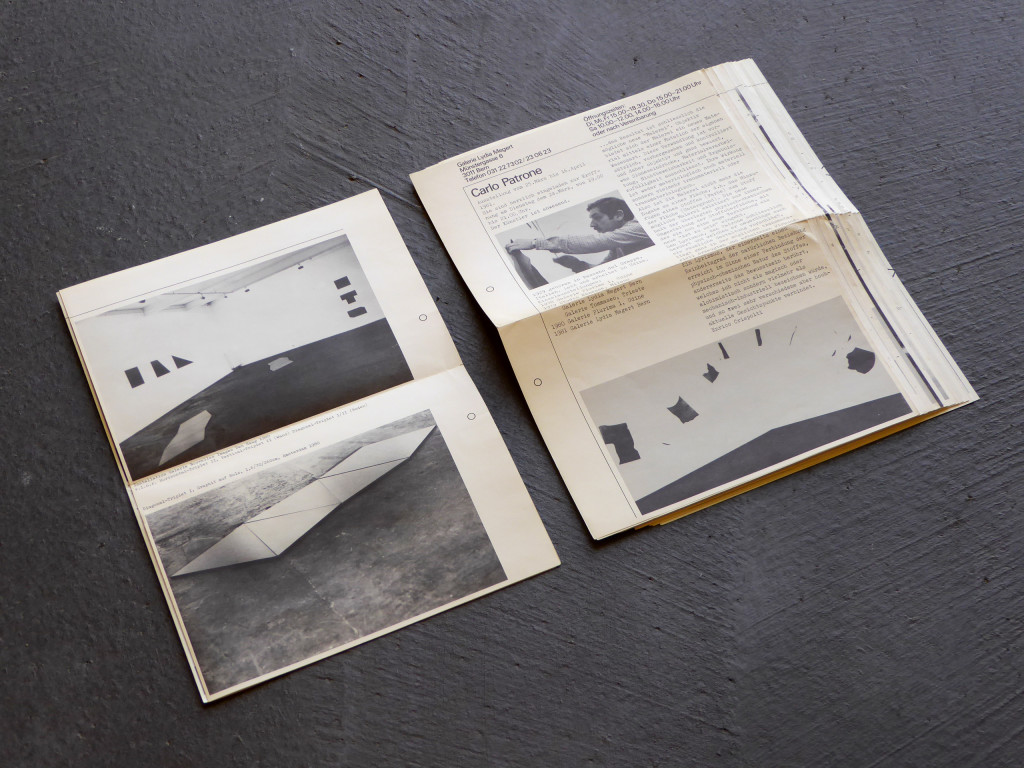

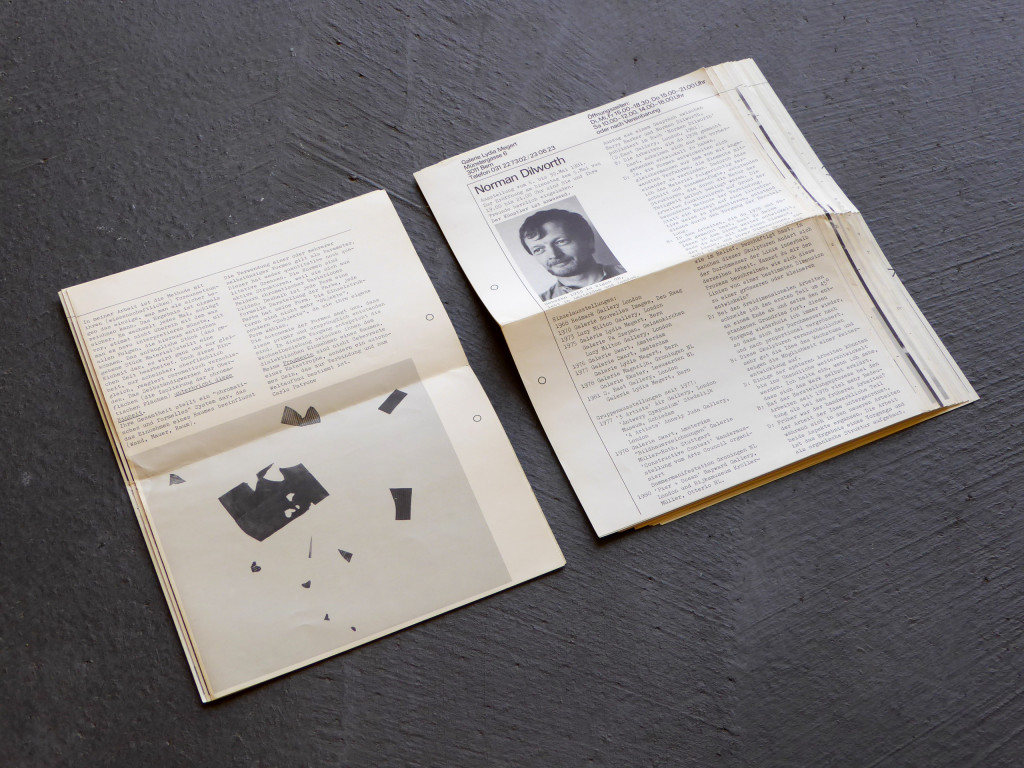

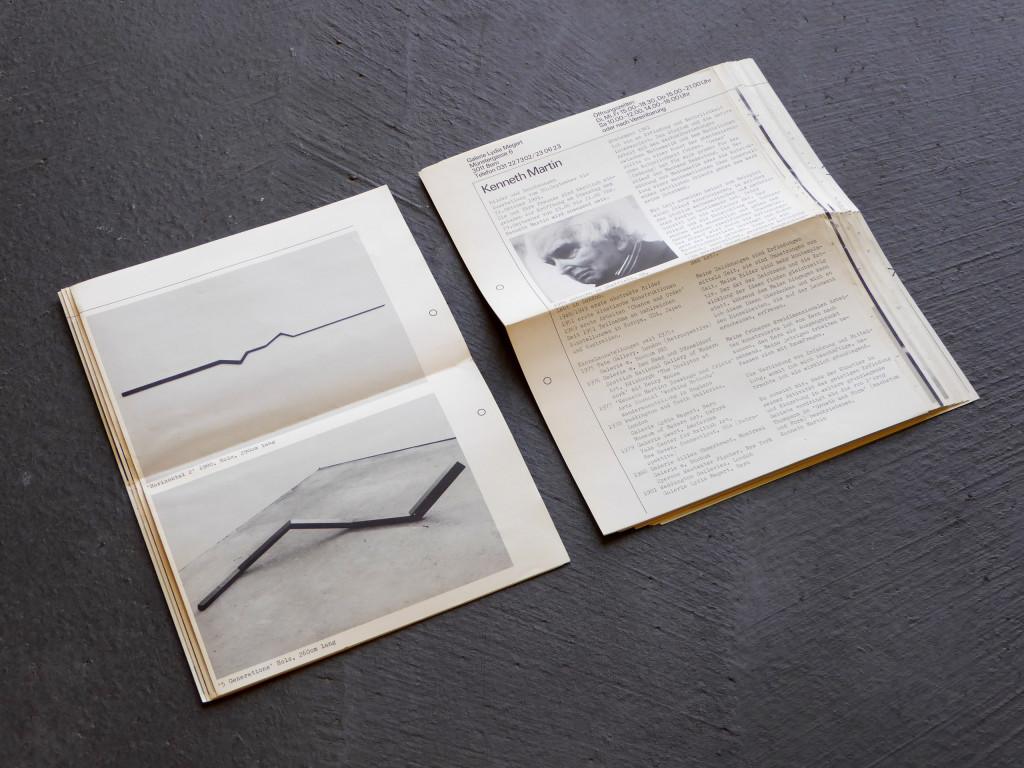

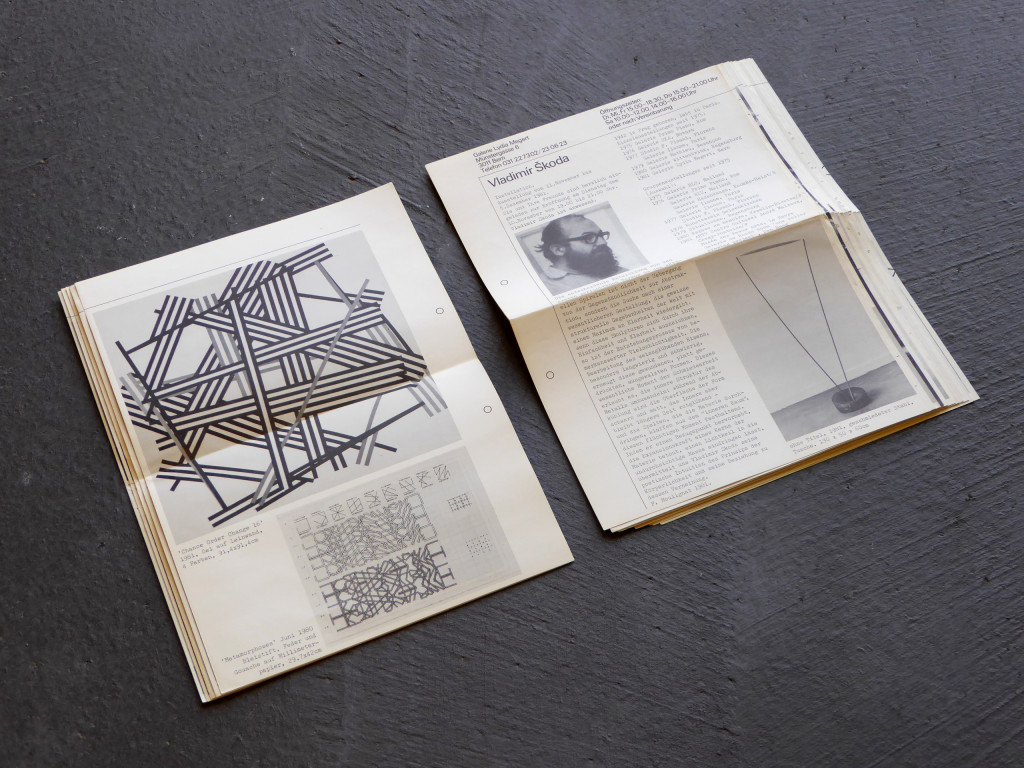

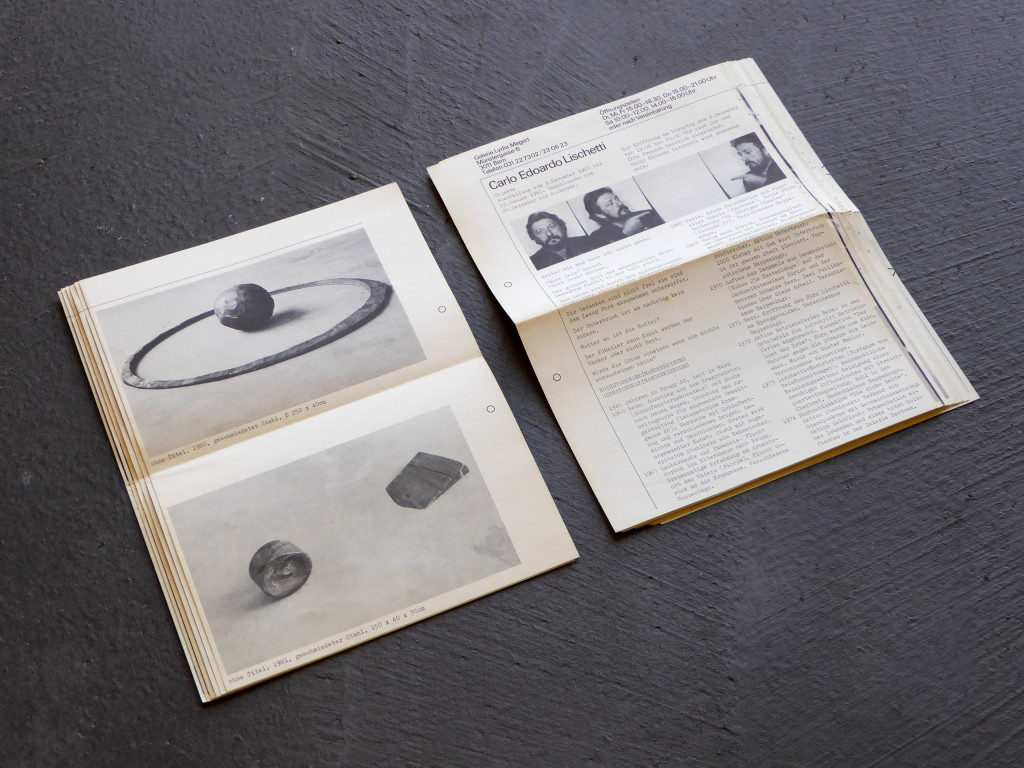

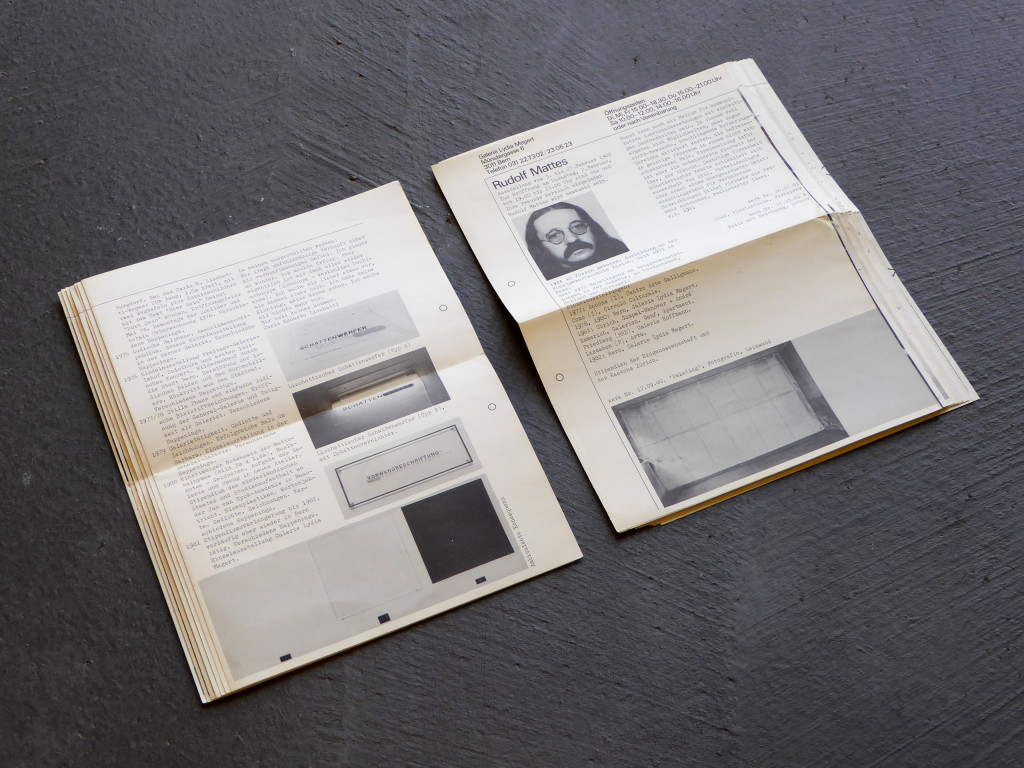

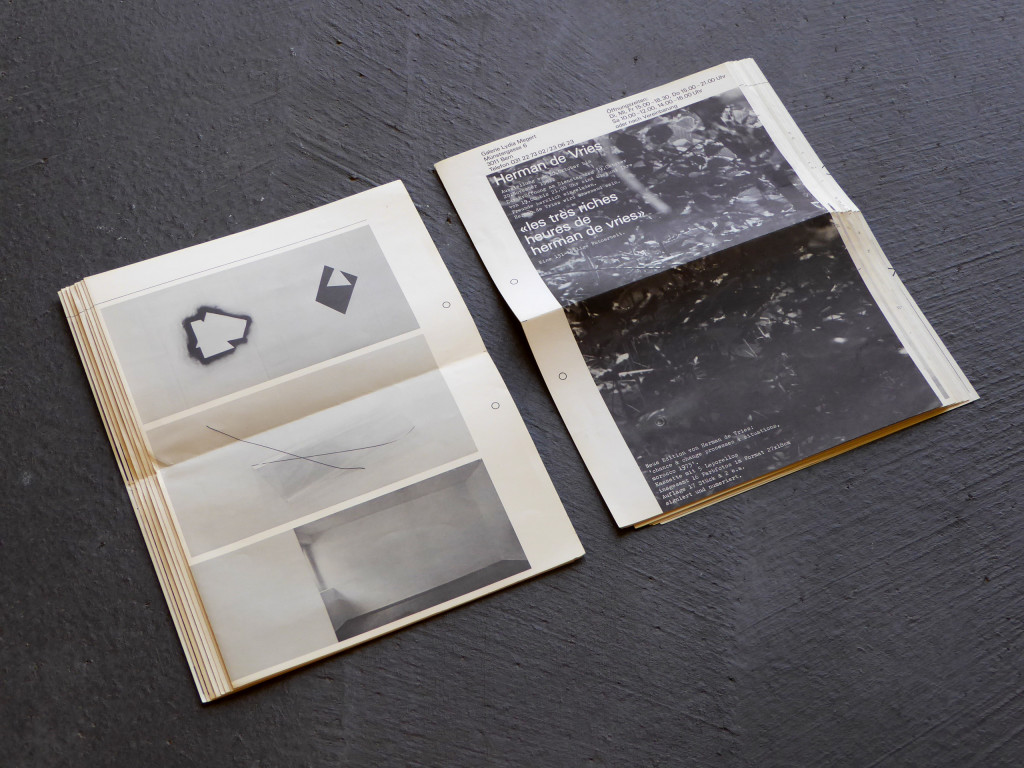

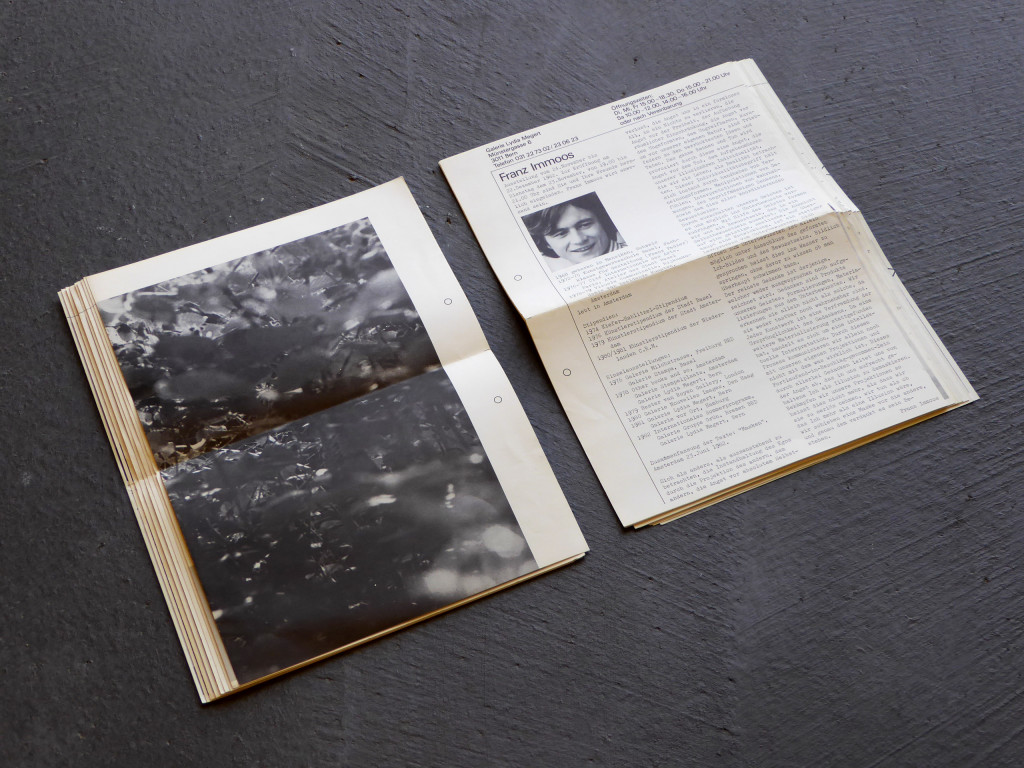

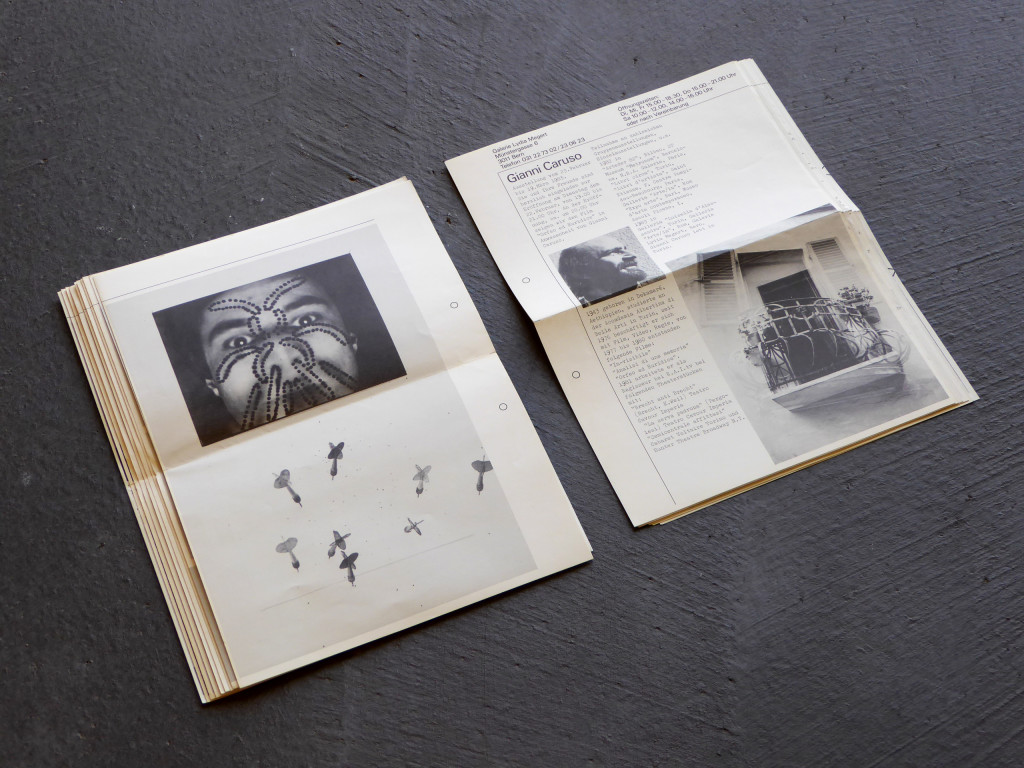

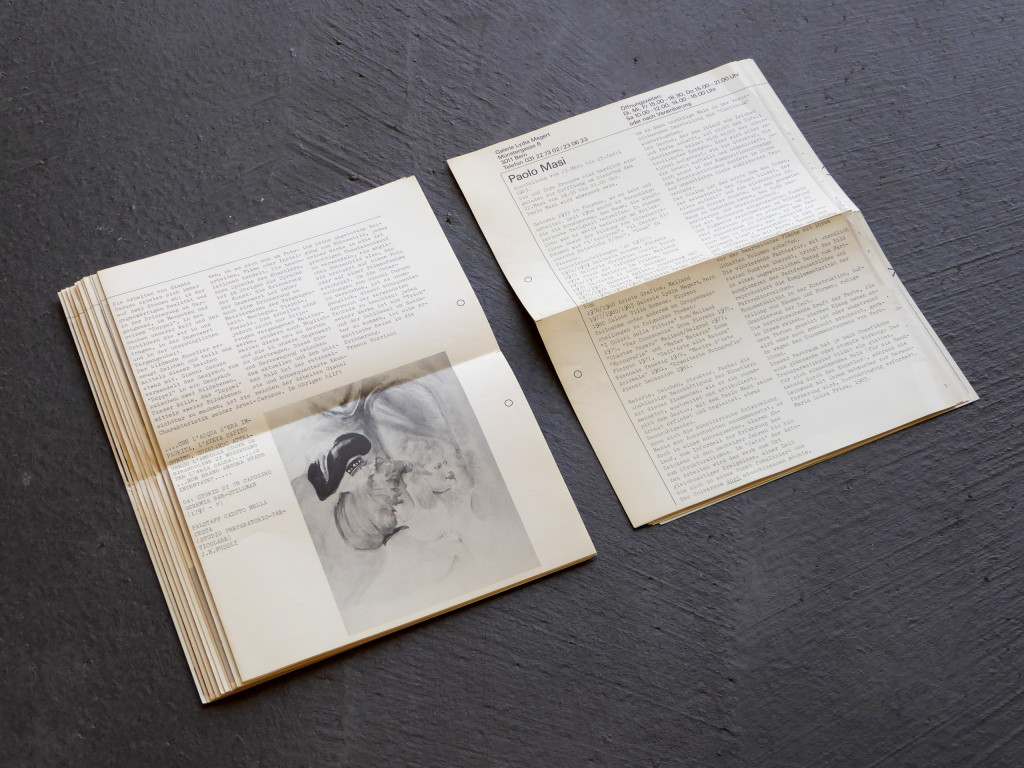

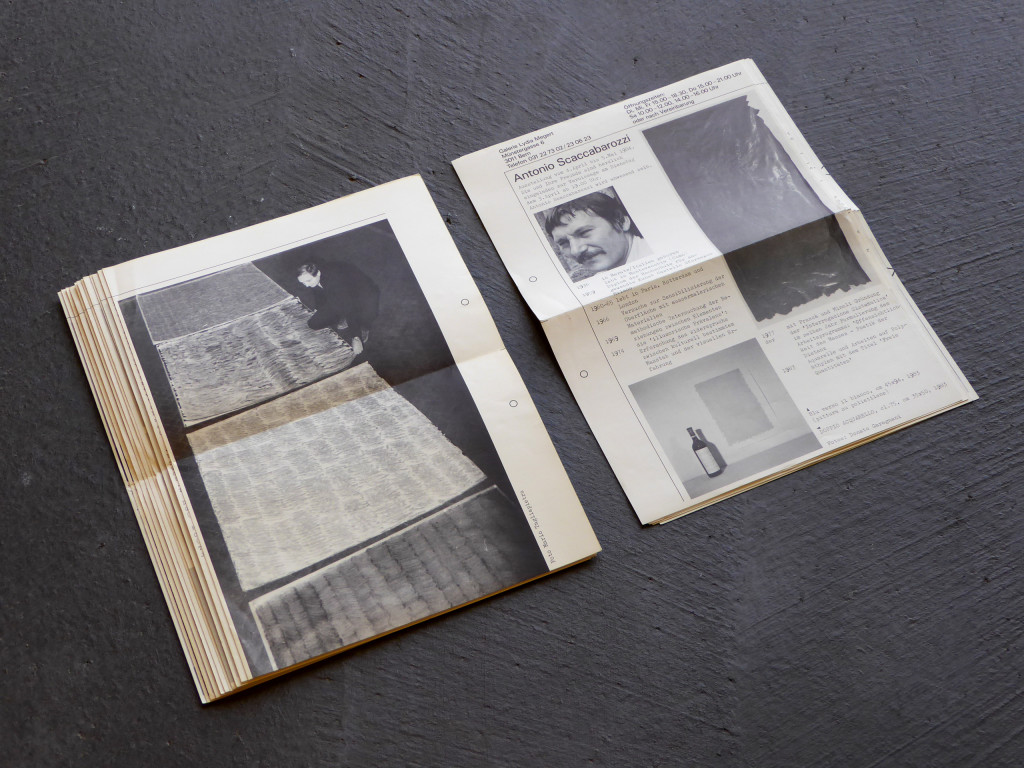

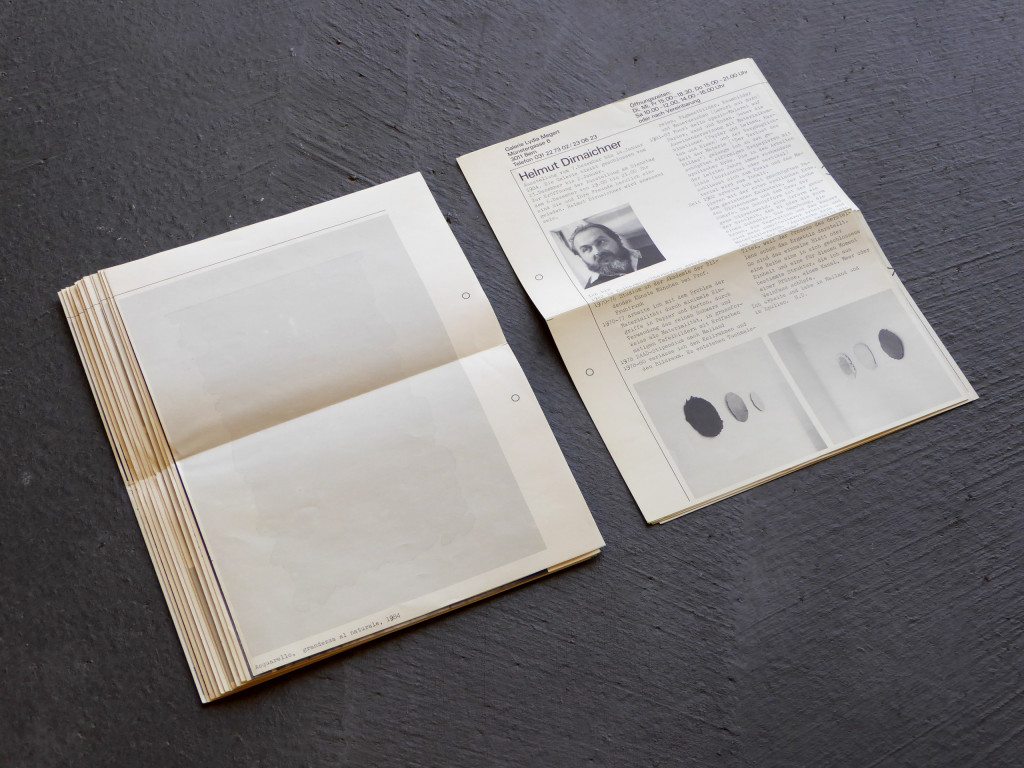

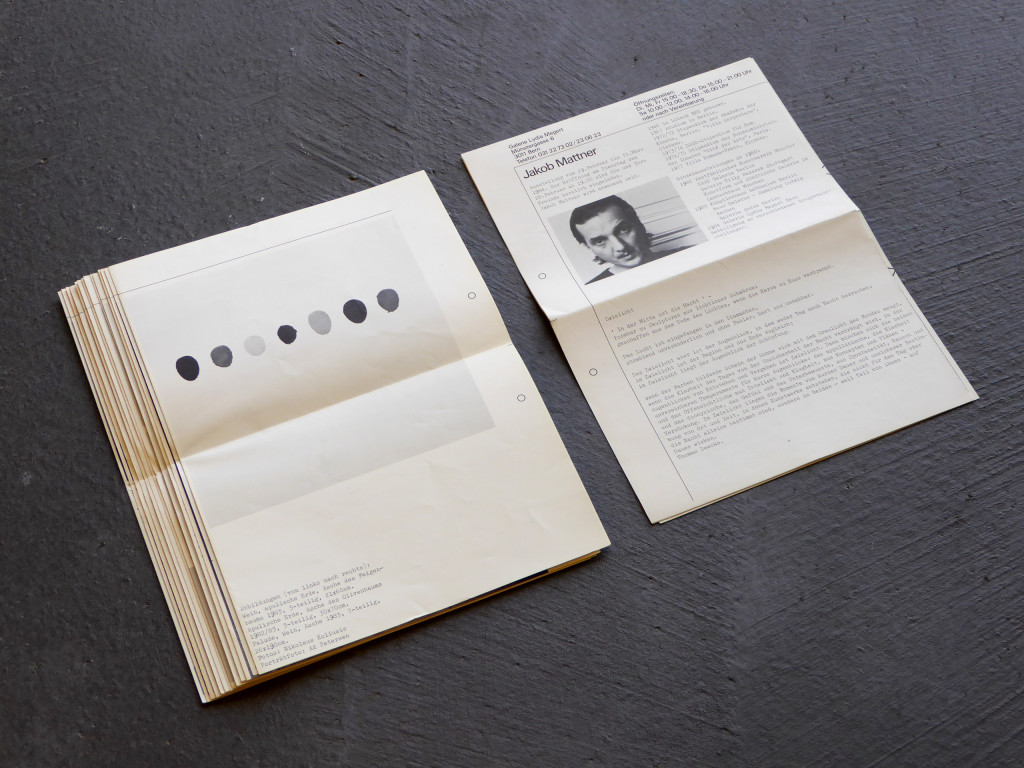

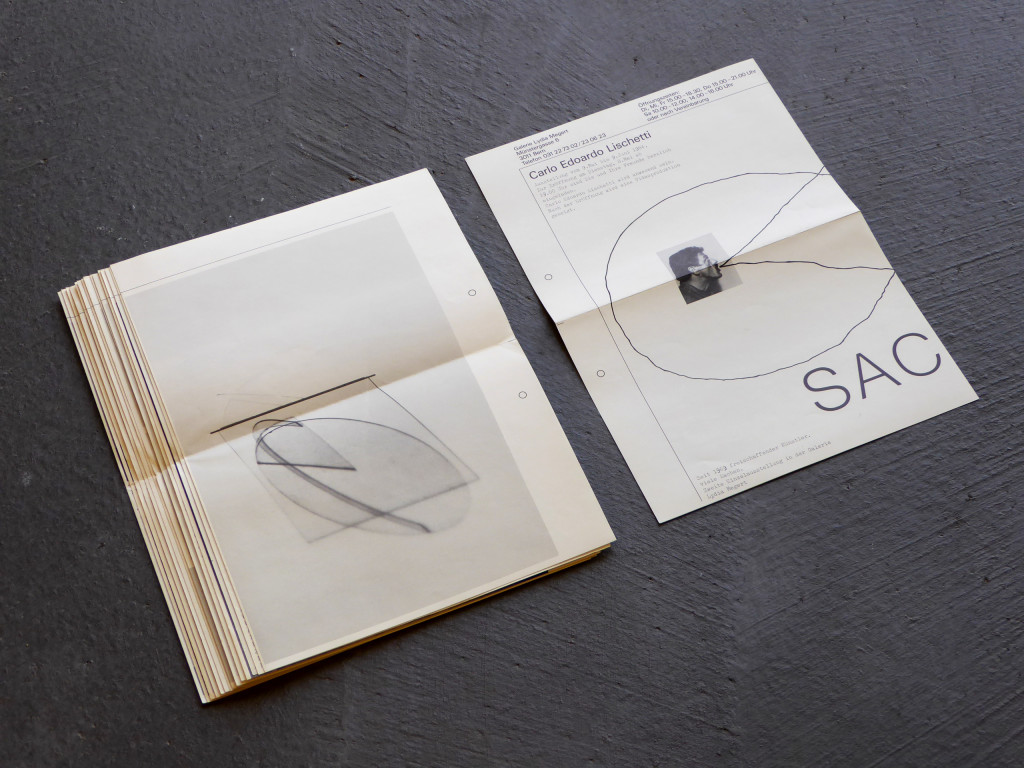

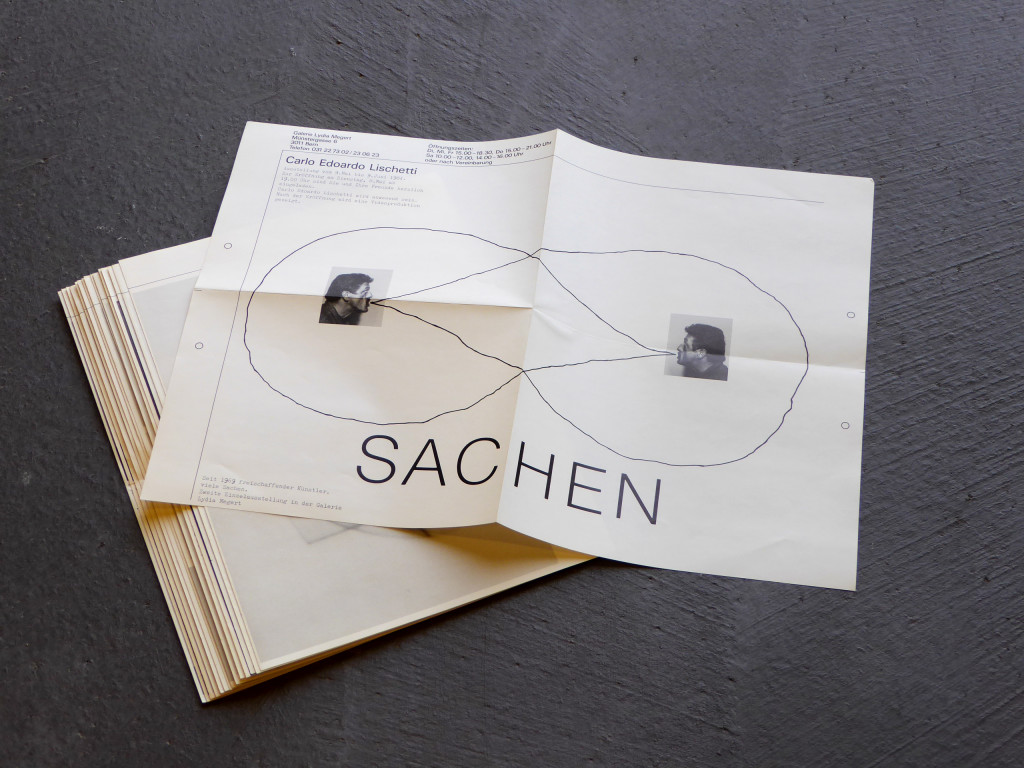

Galerie Lydia Megert, Bern

In the early 1980s the Bern based Galerie Lydia Megert produced multifunctional invitation cards on folded A3 paper. Besides the basic information on when and where the exhibitions would take place, the leaflets also contained pictures of the artists and their artworks as well as biographical overviews and short texts.

The little circles suggest that all the sheets could be punched and collected in a folder (maybe similar to Harald Szeemanns catalogs When Attitudes Become Form, 1969, and documenta 5, 1972). This way, the invitation cards could function as single pages of a potential publication documenting the history of Galerie Lydia Megert.

follow

follow